A regular file is a linear array of bytes, and can be read and written starting at any byte in the file. The kernel distinguishes no record boundaries in regular files, although many programs recognize line-feed characters as distinguishing the ends of lines, and other programs may impose other structure. No system-related information about a file is kept in the file itself, but the filesystem stores a small amount of ownership, protection, and usage information with each file.

A filename component is a string of up to 255 characters. These filenames are stored in a type of file called a directory. The information in a directory about a file is called a directory entry and includes, in addition to the filename, a pointer to the file itself. Directory entries may refer to other directories, as well as to plain files. A hierarchy of directories and files is thus formed, and is called a filesystem;

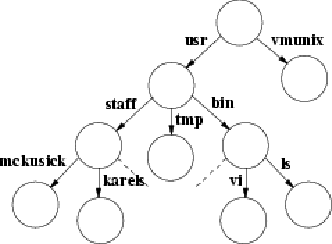

a small one is shown in Figure 2.2, “A small filesystem”. Directories may contain subdirectories, and there is no inherent limitation to the depth with which directory nesting may occur. To protect the consistency of the filesystem, the kernel does not permit processes to write directly into directories. A filesystem may include not only plain files and directories, but also references to other objects, such as devices and sockets.

The filesystem forms a tree, the beginning of which is the

root directory,

sometimes referred to by the name

slash,

spelled with a single solidus character (/).

The root directory contains files; in our example in Fig 2.2, it contains

vmunix,

a copy of the kernel-executable object file.

It also contains directories; in this example, it contains the

usr

directory.

Within the

usr

directory is the

bin

directory, which mostly contains executable object code of programs,

such as the files

ls

and

vi.

A process identifies a file by specifying that file's pathname, which is a string composed of zero or more filenames separated by slash (/) characters. The kernel associates two directories with each process for use in interpreting pathnames. A process's root directory is the topmost point in the filesystem that the process can access; it is ordinarily set to the root directory of the entire filesystem. A pathname beginning with a slash is called an absolute pathname, and is interpreted by the kernel starting with the process's root directory.

A pathname that does not begin with a slash is called a

relative pathname,

and is interpreted relative to the

current working directory

of the process.

(This directory also is known by the shorter names

current directory

or

working directory.)

The current directory itself may be referred to directly by the name

dot,

spelled with a single period

(.).

The filename

dot-dot

(..)

refers to a directory's parent directory.

The root directory is its own parent.

A process may set its root directory with the chroot system call, and its current directory with the chdir system call. Any process may do chdir at any time, but chroot is permitted only a process with superuser privileges. Chroot is normally used to set up restricted access to the system.

Using the filesystem shown in Fig. 2.2,

if a process has the root of the filesystem as its root directory, and has

/usr

as its current directory, it can refer to the file

vi

either from the root with the absolute pathname

/usr/bin/vi,

or from its current directory with the relative pathname

bin/vi.

System utilities and databases are kept in certain well-known directories.

Part of the well-defined hierarchy includes a directory that contains the

home directory

for each user -- for example,

/usr/staff/mckusick

and

/usr/staff/karels

in Fig. 2.2.

When users log in,

the current working directory of their shell is set to the

home directory.

Within their home directories,

users can create directories as easily as they can regular files.

Thus, a user can build arbitrarily complex subhierarchies.

The user usually knows of only one filesystem, but the system may know that this one virtual filesystem is really composed of several physical filesystems, each on a different device. A physical filesystem may not span multiple hardware devices. Since most physical disk devices are divided into several logical devices, there may be more than one filesystem per physical device, but there will be no more than one per logical device. One filesystem -- the filesystem that anchors all absolute pathnames -- is called the root filesystem, and is always available. Others may be mounted; that is, they may be integrated into the directory hierarchy of the root filesystem. References to a directory that has a filesystem mounted on it are converted transparently by the kernel into references to the root directory of the mounted filesystem.

The link system call takes the name of an existing file and another name to create for that file. After a successful link, the file can be accessed by either filename. A filename can be removed with the unlink system call. When the final name for a file is removed (and the final process that has the file open closes it), the file is deleted.

Files are organized hierarchically in directories. A directory is a type of file, but, in contrast to regular files, a directory has a structure imposed on it by the system. A process can read a directory as it would an ordinary file, but only the kernel is permitted to modify a directory. Directories are created by the mkdir system call and are removed by the rmdir system call. Before 4.2BSD, the mkdir and rmdir system calls were implemented by a series of link and unlink system calls being done. There were three reasons for adding systems calls explicitly to create and delete directories:

The operation could be made atomic. If the system crashed, the directory would not be left half-constructed, as could happen when a series of link operations were used.

When a networked filesystem is being run, the creation and deletion of files and directories need to be specified atomically so that they can be serialized.

When supporting non-UNIX filesystems, such as an MS-DOS filesystem, on another partition of the disk, the other filesystem may not support link operations. Although other filesystems might support the concept of directories, they probably would not create and delete the directories with links, as the UNIX filesystem does. Consequently, they could create and delete directories only if explicit directory create and delete requests were presented.

The chown system call sets the owner and group of a file, and chmod changes protection attributes. Stat applied to a filename can be used to read back such properties of a file. The fchown, fchmod, and fstat system calls are applied to a descriptor, instead of to a filename, to do the same set of operations. The rename system call can be used to give a file a new name in the filesystem, replacing one of the file's old names. Like the directory-creation and directory-deletion operations, the rename system call was added to 4.2BSD to provide atomicity to name changes in the local filesystem. Later, it proved useful explicitly to export renaming operations to foreign filesystems and over the network.

The truncate system call was added to 4.2BSD to allow files to be shortened to an arbitrary offset. The call was added primarily in support of the Fortran run-time library, which has the semantics such that the end of a random-access file is set to be wherever the program most recently accessed that file. Without the truncate system call, the only way to shorten a file was to copy the part that was desired to a new file, to delete the old file, then to rename the copy to the original name. As well as this algorithm being slow, the library could potentially fail on a full filesystem.

Once the filesystem had the ability to shorten files, the kernel took advantage of that ability to shorten large empty directories. The advantage of shortening empty directories is that it reduces the time spent in the kernel searching them when names are being created or deleted.

Newly created files are assigned the user identifier of the process that created them and the group identifier of the directory in which they were created. A three-level access-control mechanism is provided for the protection of files. These three levels specify the accessibility of a file to

The user who owns the file

The group that owns the file

Everyone else

Each level of access has separate indicators for read permission, write permission, and execute permission.

Files are created with zero length, and may grow when they are written. While a file is open, the system maintains a pointer into the file indicating the current location in the file associated with the descriptor. This pointer can be moved about in the file in a random-access fashion. Processes sharing a file descriptor through a fork or dup system call share the current location pointer. Descriptors created by separate open system calls have separate current location pointers. Files may have holes in them. Holes are void areas in the linear extent of the file where data have never been written. A process can create these holes by positioning the pointer past the current end-of-file and writing. When read, holes are treated by the system as zero-valued bytes.

Earlier UNIX systems had a limit of 14 characters per filename component.

This limitation was often a problem.

For example,

in addition to the natural desire of users

to give files long descriptive names,

a common way of forming filenames is as

basename.extension.c

for C source or

.o

for intermediate binary object)

is one to three characters,

leaving 10 to 12 characters for the basename.

Source-code-control systems and editors usually take up another

two characters, either as a prefix or a suffix, for their purposes,

leaving eight to 10 characters.

It is easy to use 10 or 12 characters in a single

English word as a basename (e.g., ``multiplexer'').

It is possible to keep within these limits,

but it is inconvenient or even dangerous, because other UNIX

systems accept strings longer than the limit when creating files,

but then

truncate

to the limit.

A C language source file named

multiplexer.c

(already 13 characters) might have a source-code-control file

with

s.

prepended, producing a filename

s.multiplexer

that is indistinguishable from the source-code-control file for

multiplexer.ms,

a file containing

troff

source for documentation for the C program.

The contents of the two original files could easily get confused

with no warning from the source-code-control system.

Careful coding can detect this problem, but the

long filenames

first introduced in 4.2BSD practically eliminate it.