The FreeBSD Documentation Project

Copyright © 1995-2021 The FreeBSD Documentation Project

Copyright

Redistribution and use in source (XML DocBook) and 'compiled'

forms (XML, HTML, PDF, PostScript, RTF and so forth) with or without

modification, are permitted provided that the following conditions are

met:

Redistributions of source code (XML DocBook) must retain the

above copyright notice, this list of conditions and the following

disclaimer as the first lines of this file unmodified.

Redistributions in compiled form (transformed to other DTDs,

converted to PDF, PostScript, RTF and other formats) must

reproduce the above copyright notice, this list of conditions and

the following disclaimer in the documentation and/or other

materials provided with the distribution.

Important:

THIS DOCUMENTATION IS PROVIDED BY THE FREEBSD DOCUMENTATION

PROJECT "AS IS" AND ANY EXPRESS OR IMPLIED WARRANTIES, INCLUDING,

BUT NOT LIMITED TO, THE IMPLIED WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY AND

FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE ARE DISCLAIMED. IN NO EVENT SHALL

THE FREEBSD DOCUMENTATION PROJECT BE LIABLE FOR ANY DIRECT, INDIRECT,

INCIDENTAL, SPECIAL, EXEMPLARY, OR CONSEQUENTIAL DAMAGES (INCLUDING,

BUT NOT LIMITED TO, PROCUREMENT OF SUBSTITUTE GOODS OR SERVICES; LOSS

OF USE, DATA, OR PROFITS; OR BUSINESS INTERRUPTION) HOWEVER CAUSED AND

ON ANY THEORY OF LIABILITY, WHETHER IN CONTRACT, STRICT LIABILITY, OR

TORT (INCLUDING NEGLIGENCE OR OTHERWISE) ARISING IN ANY WAY OUT OF THE

USE OF THIS DOCUMENTATION, EVEN IF ADVISED OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH

DAMAGE.

FreeBSD is a registered trademark of

the FreeBSD Foundation.

3Com and HomeConnect are registered

trademarks of 3Com Corporation.

3ware is a registered

trademark of 3ware Inc.

ARM is a registered trademark of ARM

Limited.

Adaptec is a registered trademark of

Adaptec, Inc.

Adobe, Acrobat, Acrobat Reader, Flash and

PostScript are either registered trademarks or trademarks of Adobe

Systems Incorporated in the United States and/or other

countries.

Apple, AirPort, FireWire,

iMac, iPhone, iPad,

Mac, Macintosh, Mac OS,

Quicktime, and TrueType are trademarks of Apple Inc.,

registered in the U.S. and other countries.

Android

is a trademark of Google Inc.

Heidelberg, Helvetica,

Palatino, and Times Roman are either registered trademarks or

trademarks of Heidelberger Druckmaschinen AG in the U.S. and other

countries.

IBM, AIX, OS/2,

PowerPC, PS/2, S/390, and ThinkPad are

trademarks of International Business Machines Corporation in the

United States, other countries, or both.

IEEE, POSIX, and 802 are registered

trademarks of Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers,

Inc. in the United States.

Intel, Celeron, Centrino, Core, EtherExpress, i386,

i486, Itanium, Pentium, and Xeon are trademarks or registered

trademarks of Intel Corporation or its subsidiaries in the United

States and other countries.

Intuit and Quicken are registered

trademarks and/or registered service marks of Intuit Inc., or one of

its subsidiaries, in the United States and other countries.

Linux is a registered trademark of

Linus Torvalds.

LSI Logic, AcceleRAID, eXtremeRAID,

MegaRAID and Mylex are trademarks or registered trademarks of LSI

Logic Corp.

Microsoft, IntelliMouse, MS-DOS,

Outlook, Windows, Windows Media and Windows NT are either

registered trademarks or trademarks of Microsoft Corporation in the

United States and/or other countries.

Motif, OSF/1, and UNIX are

registered trademarks and IT DialTone and The Open Group are

trademarks of The Open Group in the United States and other

countries.

Oracle is a registered trademark

of Oracle Corporation.

RealNetworks, RealPlayer, and

RealAudio are the registered trademarks of RealNetworks,

Inc.

Red Hat, RPM, are trademarks or

registered trademarks of Red Hat, Inc. in the United States and

other countries.

Sun, Sun Microsystems, Java, Java

Virtual Machine, JDK, JRE, JSP, JVM, Netra, OpenJDK,

Solaris, StarOffice, SunOS

and VirtualBox are trademarks or registered trademarks of

Sun Microsystems, Inc. in the United States and other countries.

MATLAB is a registered trademark

of The MathWorks, Inc.

SpeedTouch is a trademark of

Thomson.

VMware is a trademark of VMware,

Inc.

Mathematica is a registered

trademark of Wolfram Research, Inc.

XFree86 is a trademark of The

XFree86 Project, Inc.

Ogg Vorbis and Xiph.Org are trademarks

of Xiph.Org.

Many of the designations used by

manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed

as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this document,

and the FreeBSD Project was aware of the trademark claim, the

designations have been followed by the “™” or the

“®” symbol.

Last modified on 2021-05-08 01:17:39 WIB by root.

Abstract

Welcome to FreeBSD! This handbook covers the installation

and day to day use of

FreeBSD 13.0-RELEASE,

FreeBSD 12.2-RELEASE, and

FreeBSD 11.4-RELEASE. This book

is the result of ongoing work by many individuals. Some

sections might be outdated. Those interested in helping to

update and expand this document should send email to the

FreeBSD documentation project mailing list.

The latest version of this book is available from the

FreeBSD web

site. Previous versions can be obtained from https://docs.FreeBSD.org/doc/.

The book can be downloaded in a variety of formats and

compression options from the FreeBSD

FTP server or one of the numerous

mirror sites. Printed

copies can be purchased at the

FreeBSD

Mall. Searches can be performed on the handbook and

other documents on the

search

page.

Intended

Audience

The FreeBSD newcomer will find that the first section of this

book guides the user through the FreeBSD installation process and

gently introduces the concepts and conventions that underpin

UNIX®. Working through this section requires little more than

the desire to explore, and the ability to take on board new

concepts as they are introduced.

Once you have traveled this far, the second, far larger,

section of the Handbook is a comprehensive reference to all manner

of topics of interest to FreeBSD system administrators. Some of

these chapters may recommend that you do some prior reading, and

this is noted in the synopsis at the beginning of each

chapter.

For a list of additional sources of information, please see

Appendix B, Bibliography.

Changes

from the Third Edition

The current online version of the Handbook represents the

cumulative effort of many hundreds of contributors over the past

10 years. The following are some of the significant changes since

the two volume third edition was published in 2004:

Changes

from the Second Edition (2004)

The third edition was the culmination of over two years of

work by the dedicated members of the FreeBSD Documentation

Project. The printed edition grew to such a size that it was

necessary to publish as two separate volumes. The following are

the major changes in this new edition:

Chapter 12, Configuration and Tuning has been expanded with new

information about the ACPI power and resource management, the

cron system utility, and more kernel tuning

options.

Chapter 14, Security has been expanded with new

information about virtual private networks (VPNs), file system

access control lists (ACLs), and security advisories.

Chapter 16, Mandatory Access Control is a new chapter with this edition.

It explains what MAC is and how this mechanism can be used to

secure a FreeBSD system.

Chapter 18, Storage has been expanded with new

information about USB storage devices, file system snapshots,

file system quotas, file and network backed filesystems, and

encrypted disk partitions.

A troubleshooting section has been added to Chapter 28, PPP.

Chapter 29, Electronic Mail has been expanded with new

information about using alternative transport agents, SMTP

authentication, UUCP, fetchmail,

procmail, and other advanced

topics.

Chapter 30, Network Servers is all new with this

edition. This chapter includes information about setting up

the Apache HTTP Server,

ftpd, and setting up a server for

Microsoft® Windows® clients with

Samba. Some sections from Chapter 32, Advanced Networking were moved here to improve

the presentation.

Chapter 32, Advanced Networking has been expanded

with new information about using Bluetooth® devices with

FreeBSD, setting up wireless networks, and Asynchronous Transfer

Mode (ATM) networking.

A glossary has been added to provide a central location

for the definitions of technical terms used throughout the

book.

A number of aesthetic improvements have been made to the

tables and figures throughout the book.

Changes from

the First Edition (2001)

The second edition was the culmination of over two years of

work by the dedicated members of the FreeBSD Documentation Project.

The following were the major changes in this edition:

A complete Index has been added.

All ASCII figures have been replaced by graphical

diagrams.

A standard synopsis has been added to each chapter to

give a quick summary of what information the chapter

contains, and what the reader is expected to know.

The content has been logically reorganized into three

parts: “Getting Started”, “System

Administration”, and

“Appendices”.

Chapter 3, FreeBSD Basics has been expanded to contain

additional information about processes, daemons, and

signals.

Chapter 4, Installing Applications: Packages and Ports has been expanded to contain

additional information about binary package

management.

Chapter 5, The X Window System has been completely rewritten with

an emphasis on using modern desktop technologies such as

KDE and

GNOME on XFree86™ 4.X.

Chapter 13, The FreeBSD Booting Process has been expanded.

Chapter 18, Storage has been written from what used

to be two separate chapters on “Disks” and

“Backups”. We feel that the topics are easier

to comprehend when presented as a single chapter. A section

on RAID (both hardware and software) has also been

added.

Chapter 27, Serial Communications has been completely

reorganized and updated for FreeBSD 4.X/5.X.

Chapter 28, PPP has been substantially

updated.

Many new sections have been added to Chapter 32, Advanced Networking.

Chapter 29, Electronic Mail has been expanded to include more

information about configuring

sendmail.

Chapter 10, Linux® Binary Compatibility has been expanded to include

information about installing

Oracle® and

SAP® R/3®.

The following new topics are covered in this second

edition:

Organization of This Book

This book is split into five logically distinct sections.

The first section, Getting Started, covers

the installation and basic usage of FreeBSD. It is expected that

the reader will follow these chapters in sequence, possibly

skipping chapters covering familiar topics. The second section,

Common Tasks, covers some frequently used

features of FreeBSD. This section, and all subsequent sections,

can be read out of order. Each chapter begins with a succinct

synopsis that describes what the chapter covers and what the

reader is expected to already know. This is meant to allow the

casual reader to skip around to find chapters of interest. The

third section, System Administration, covers

administration topics. The fourth section, Network

Communication, covers networking and server topics.

The fifth section contains appendices of reference

information.

- Chapter 1, Introduction

Introduces FreeBSD to a new user. It describes the

history of the FreeBSD Project, its goals and development

model.

- Chapter 2, Installing FreeBSD

Walks a user through the entire installation process of

FreeBSD 9.x and later using

bsdinstall.

- Chapter 3, FreeBSD Basics

Covers the basic commands and functionality of the

FreeBSD operating system. If you are familiar with Linux®

or another flavor of UNIX® then you can probably skip this

chapter.

- Chapter 4, Installing Applications: Packages and Ports

Covers the installation of third-party software with

both FreeBSD's innovative “Ports Collection” and

standard binary packages.

- Chapter 5, The X Window System

Describes the X Window System in general and using X11

on FreeBSD in particular. Also describes common desktop

environments such as KDE and

GNOME.

- Chapter 6, Desktop Applications

Lists some common desktop applications, such as web

browsers and productivity suites, and describes how to

install them on FreeBSD.

- Chapter 7, Multimedia

Shows how to set up sound and video playback support

for your system. Also describes some sample audio and video

applications.

- Chapter 8, Configuring the FreeBSD Kernel

Explains why you might need to configure a new kernel

and provides detailed instructions for configuring,

building, and installing a custom kernel.

- Chapter 9, Printing

Describes managing printers on FreeBSD, including

information about banner pages, printer accounting, and

initial setup.

- Chapter 10, Linux® Binary Compatibility

Describes the Linux® compatibility features of FreeBSD.

Also provides detailed installation instructions for many

popular Linux® applications such as

Oracle® and

Mathematica®.

- Chapter 12, Configuration and Tuning

Describes the parameters available for system

administrators to tune a FreeBSD system for optimum

performance. Also describes the various configuration files

used in FreeBSD and where to find them.

- Chapter 13, The FreeBSD Booting Process

Describes the FreeBSD boot process and explains how to

control this process with configuration options.

- Chapter 14, Security

Describes many different tools available to help keep

your FreeBSD system secure, including Kerberos, IPsec and

OpenSSH.

- Chapter 15, Jails

Describes the jails framework, and the improvements of

jails over the traditional chroot support of FreeBSD.

- Chapter 16, Mandatory Access Control

Explains what Mandatory Access Control (MAC) is and

how this mechanism can be used to secure a FreeBSD

system.

- Chapter 17, Security Event Auditing

Describes what FreeBSD Event Auditing is, how it can be

installed, configured, and how audit trails can be inspected

or monitored.

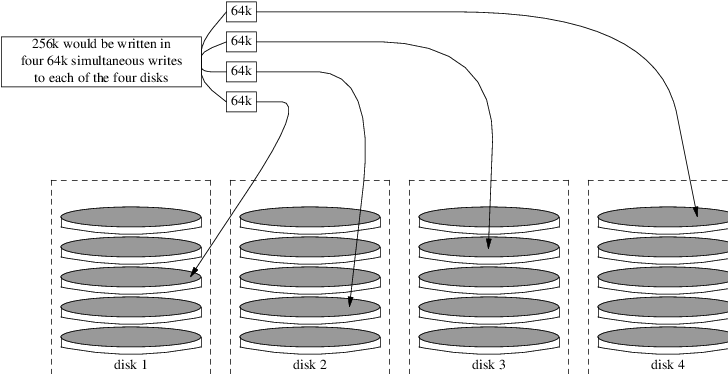

- Chapter 18, Storage

Describes how to manage storage media and filesystems

with FreeBSD. This includes physical disks, RAID arrays,

optical and tape media, memory-backed disks, and network

filesystems.

- Chapter 19, GEOM: Modular Disk Transformation Framework

Describes what the GEOM framework in FreeBSD is and how

to configure various supported RAID levels.

- Chapter 21, Other File Systems

Examines support of non-native file systems in FreeBSD,

like the Z File System from Sun™.

- Chapter 22, Virtualization

Describes what virtualization systems offer, and how

they can be used with FreeBSD.

- Chapter 23, Localization -

i18n/L10n Usage and

Setup

Describes how to use FreeBSD in languages other than

English. Covers both system and application level

localization.

- Chapter 24, Updating and Upgrading FreeBSD

Explains the differences between FreeBSD-STABLE,

FreeBSD-CURRENT, and FreeBSD releases. Describes which users

would benefit from tracking a development system and

outlines that process. Covers the methods users may take

to update their system to the latest security

release.

- Chapter 25, DTrace

Describes how to configure and use the DTrace tool

from Sun™ in FreeBSD. Dynamic tracing can help locate

performance issues, by performing real time system

analysis.

- Chapter 27, Serial Communications

Explains how to connect terminals and modems to your

FreeBSD system for both dial in and dial out

connections.

- Chapter 28, PPP

Describes how to use PPP to connect to remote systems

with FreeBSD.

- Chapter 29, Electronic Mail

Explains the different components of an email server

and dives into simple configuration topics for the most

popular mail server software:

sendmail.

- Chapter 30, Network Servers

Provides detailed instructions and example configuration

files to set up your FreeBSD machine as a network filesystem

server, domain name server, network information system

server, or time synchronization server.

- Chapter 31, Firewalls

Explains the philosophy behind software-based firewalls

and provides detailed information about the configuration

of the different firewalls available for FreeBSD.

- Chapter 32, Advanced Networking

Describes many networking topics, including sharing an

Internet connection with other computers on your LAN,

advanced routing topics, wireless networking, Bluetooth®,

ATM, IPv6, and much more.

- Appendix A, Obtaining FreeBSD

Lists different sources for obtaining FreeBSD media on

CDROM or DVD as well as different sites on the Internet

that allow you to download and install FreeBSD.

- Appendix B, Bibliography

This book touches on many different subjects that may

leave you hungry for a more detailed explanation. The

bibliography lists many excellent books that are referenced

in the text.

- Appendix C, Resources on the Internet

Describes the many forums available for FreeBSD users to

post questions and engage in technical conversations about

FreeBSD.

- Appendix D, OpenPGP Keys

Lists the PGP fingerprints of several FreeBSD

Developers.

Conventions used

in this book

To provide a consistent and easy to read text, several

conventions are followed throughout the book.

Typographic Conventions

- Italic

An italic font is used for

filenames, URLs, emphasized text, and the first usage of

technical terms.

MonospaceA monospaced font is used for error

messages, commands, environment variables, names of ports,

hostnames, user names, group names, device names, variables,

and code fragments.

- Bold

A bold font is used for

applications, commands, and keys.

User

Input

Keys are shown in bold to stand out from

other text. Key combinations that are meant to be typed

simultaneously are shown with `+' between

the keys, such as:

Ctrl+Alt+Del

Meaning the user should type the Ctrl,

Alt, and Del keys at the same

time.

Keys that are meant to be typed in sequence will be separated

with commas, for example:

Ctrl+X,

Ctrl+S

Would mean that the user is expected to type the

Ctrl and X keys simultaneously

and then to type the Ctrl and S

keys simultaneously.

Examples

Examples starting with C:\>

indicate a MS-DOS® command. Unless otherwise noted, these

commands may be executed from a “Command Prompt”

window in a modern Microsoft® Windows®

environment.

E:\> tools\fdimage floppies\kern.flp A:

Examples starting with # indicate a command that

must be invoked as the superuser in FreeBSD. You can login as

root to type the

command, or login as your normal account and use su(1) to

gain superuser privileges.

# dd if=kern.flp of=/dev/fd0

Examples starting with % indicate a command that

should be invoked from a normal user account. Unless otherwise

noted, C-shell syntax is used for setting environment variables

and other shell commands.

% top

Acknowledgments

The book you are holding represents the efforts of many

hundreds of people around the world. Whether they sent in fixes

for typos, or submitted complete chapters, all the contributions

have been useful.

Several companies have supported the development of this

document by paying authors to work on it full-time, paying for

publication, etc. In particular, BSDi (subsequently acquired by

Wind River

Systems) paid members of the FreeBSD Documentation Project

to work on improving this book full time leading up to the

publication of the first printed edition in March 2000 (ISBN

1-57176-241-8). Wind River Systems then paid several additional

authors to make a number of improvements to the print-output

infrastructure and to add additional chapters to the text. This

work culminated in the publication of the second printed edition

in November 2001 (ISBN 1-57176-303-1). In 2003-2004, FreeBSD Mall, Inc,

paid several contributors to improve the Handbook in preparation

for the third printed edition.

This part of the handbook is for users and administrators

who are new to FreeBSD. These chapters:

Introduce FreeBSD.

Guide readers through the installation process.

Teach UNIX® basics and fundamentals.

Show how to install the wealth of third party

applications available for FreeBSD.

Introduce X, the UNIX® windowing system, and detail

how to configure a desktop environment that makes users

more productive.

The number of forward references in the text have been

kept to a minimum so that this section can be read from front

to back with minimal page flipping.

Restructured, reorganized, and parts rewritten

by Jim Mock.

Thank you for your interest in FreeBSD! The following chapter

covers various aspects of the FreeBSD Project, such as its

history, goals, development model, and so on.

After reading this chapter you will know:

How FreeBSD relates to other computer operating

systems.

The history of the FreeBSD Project.

The goals of the FreeBSD Project.

The basics of the FreeBSD open-source development

model.

And of course: where the name “FreeBSD” comes

from.

FreeBSD is an Open Source, standards-compliant Unix-like

operating system for x86 (both 32 and 64 bit), ARM®, AArch64,

RISC-V®, MIPS®, POWER®, PowerPC®, and Sun UltraSPARC®

computers. It provides all the features that are

nowadays taken for granted, such as preemptive multitasking,

memory protection, virtual memory, multi-user facilities, SMP

support, all the Open Source development tools for different

languages and frameworks, and desktop features centered around

X Window System, KDE, or GNOME. Its particular strengths

are:

Liberal Open Source license,

which grants you rights to freely modify and extend

its source code and incorporate it in both Open Source

projects and closed products without imposing

restrictions typical to copyleft licenses, as well

as avoiding potential license incompatibility

problems.

Strong TCP/IP networking

- FreeBSD

implements industry standard protocols with ever

increasing performance and scalability. This makes

it a good match in both server, and routing/firewalling

roles - and indeed many companies and vendors use it

precisely for that purpose.

Fully integrated OpenZFS support,

including root-on-ZFS, ZFS Boot Environments, fault

management, administrative delegation, support for jails,

FreeBSD specific documentation, and system installer

support.

Extensive security features,

from the Mandatory Access Control framework to Capsicum

capability and sandbox mechanisms.

Over 30 thousand prebuilt

packages for all supported architectures,

and the Ports Collection which makes it easy to build your

own, customized ones.

Documentation - in addition

to Handbook and books from different authors that cover

topics ranging from system administration to kernel

internals, there are also the man(1) pages, not only

for userspace daemons, utilities, and configuration files,

but also for kernel driver APIs (section 9) and individual

drivers (section 4).

Simple and consistent repository structure

and build system - FreeBSD uses a single

repository for all of its components, both kernel and

userspace. This, along with an unified and easy to

customize build system and a well thought out development

process makes it easy to integrate FreeBSD with build

infrastructure for your own product.

Staying true to Unix philosophy,

preferring composability instead of monolithic “all

in one” daemons with hardcoded behavior.

Binary compatibility with Linux,

which makes it possible to run many Linux binaries without

the need for virtualisation.

FreeBSD is based on the 4.4BSD-Lite release from Computer

Systems Research Group (CSRG) at the University of California at Berkeley, and

carries on the distinguished tradition of BSD systems

development. In addition to the fine work provided by CSRG,

the FreeBSD Project has put in many thousands of man-hours

into extending the functionality and fine-tuning the system

for maximum performance and reliability

in real-life load situations. FreeBSD offers performance and

reliability on par with other Open Source and commercial

offerings, combined with cutting-edge features not available

anywhere else.

1.2.1. What Can FreeBSD Do?

The applications to which FreeBSD can be put are truly

limited only by your own imagination. From software

development to factory automation, inventory control to

azimuth correction of remote satellite antennae; if it can be

done with a commercial UNIX® product then it is more than

likely that you can do it with FreeBSD too! FreeBSD also benefits

significantly from literally thousands of high quality

applications developed by research centers and universities

around the world, often available at little to no cost.

Because the source code for FreeBSD itself is freely

available, the system can also be customized to an almost

unheard of degree for special applications or projects, and in

ways not generally possible with operating systems from most

major commercial vendors. Here is just a sampling of some of

the applications in which people are currently using

FreeBSD:

Internet Services: The robust

TCP/IP networking built into FreeBSD makes it an ideal

platform for a variety of Internet services such

as:

Education: Are you a student of

computer science or a related engineering field? There

is no better way of learning about operating systems,

computer architecture and networking than the hands on,

under the hood experience that FreeBSD can provide. A number

of freely available CAD, mathematical and graphic design

packages also make it highly useful to those whose primary

interest in a computer is to get

other work done!

Research: With source code for

the entire system available, FreeBSD is an excellent platform

for research in operating systems as well as other

branches of computer science. FreeBSD's freely available

nature also makes it possible for remote groups to

collaborate on ideas or shared development without having

to worry about special licensing agreements or limitations

on what may be discussed in open forums.

Networking: Need a new

router? A name server (DNS)? A firewall to keep people out of your

internal network? FreeBSD can easily turn that unused

PC sitting in the corner into an advanced router with

sophisticated packet-filtering capabilities.

Embedded: FreeBSD makes an

excellent platform to build embedded systems upon.

With support for the ARM®, MIPS® and PowerPC®

platforms, coupled with a robust network stack, cutting

edge features and the permissive BSD

license FreeBSD makes an excellent foundation for

building embedded routers, firewalls, and other

devices.

Desktop: FreeBSD makes a

fine choice for an inexpensive desktop solution

using the freely available X11 server.

FreeBSD offers a choice from many open-source desktop

environments, including the standard

GNOME and

KDE graphical user interfaces.

FreeBSD can even boot “diskless” from

a central server, making individual workstations

even cheaper and easier to administer.

Software Development: The basic

FreeBSD system comes with a full suite of development

tools including a full

C/C++

compiler and debugger suite.

Support for many other languages are also available

through the ports and packages collection.

FreeBSD is available to download free of charge, or can be

obtained on either CD-ROM or DVD. Please see

Appendix A, Obtaining FreeBSD for more information about obtaining

FreeBSD.

FreeBSD has been known for its web serving capabilities -

sites that run on FreeBSD include

Hacker News,

Netcraft,

NetEase,

Netflix,

Sina,

Sony Japan,

Rambler,

Yahoo!, and

Yandex.

FreeBSD's advanced features, proven security, predictable

release cycle, and permissive license have led to its use as a

platform for building many commercial and open source

appliances, devices, and products. Many of the world's

largest IT companies use FreeBSD:

Apache

- The Apache Software Foundation runs most of

its public facing infrastructure, including possibly one

of the largest SVN repositories in the world with over 1.4

million commits, on FreeBSD.

Apple

- OS X borrows heavily from FreeBSD for the

network stack, virtual file system, and many userland

components. Apple iOS also contains elements borrowed

from FreeBSD.

Cisco

- IronPort network security and anti-spam

appliances run a modified FreeBSD kernel.

Citrix

- The NetScaler line of security appliances

provide layer 4-7 load balancing, content caching,

application firewall, secure VPN, and mobile cloud network

access, along with the power of a FreeBSD shell.

Dell EMC Isilon

- Isilon's enterprise storage appliances

are based on FreeBSD. The extremely liberal FreeBSD license

allowed Isilon to integrate their intellectual property

throughout the kernel and focus on building their product

instead of an operating system.

Quest

KACE

- The KACE system management appliances run

FreeBSD because of its reliability, scalability, and the

community that supports its continued development.

iXsystems

- The TrueNAS line of unified storage

appliances is based on FreeBSD. In addition to their

commercial products, iXsystems also manages development of

the open source projects TrueOS and FreeNAS.

Juniper

- The JunOS operating system that powers all

Juniper networking gear (including routers, switches,

security, and networking appliances) is based on FreeBSD.

Juniper is one of many vendors that showcases the

symbiotic relationship between the project and vendors of

commercial products. Improvements generated at Juniper

are upstreamed into FreeBSD to reduce the complexity of

integrating new features from FreeBSD back into JunOS in the

future.

McAfee

- SecurOS, the basis of McAfee enterprise

firewall products including Sidewinder is based on

FreeBSD.

NetApp

- The Data ONTAP GX line of storage

appliances are based on FreeBSD. In addition, NetApp has

contributed back many features, including the new BSD

licensed hypervisor, bhyve.

Netflix

- The OpenConnect appliance that Netflix

uses to stream movies to its customers is based on FreeBSD.

Netflix has made extensive contributions to the codebase

and works to maintain a zero delta from mainline FreeBSD.

Netflix OpenConnect appliances are responsible for

delivering more than 32% of all Internet traffic in North

America.

Sandvine

- Sandvine uses FreeBSD as the basis of their

high performance real-time network processing platforms

that make up their intelligent network policy control

products.

Sony

- The PlayStation 4 gaming console runs a

modified version of FreeBSD.

Sophos

- The Sophos Email Appliance product is based

on a hardened FreeBSD and scans inbound mail for spam and

viruses, while also monitoring outbound mail for malware

as well as the accidental loss of sensitive

information.

Spectra

Logic

- The nTier line of archive grade storage

appliances run FreeBSD and OpenZFS.

Stormshield

- Stormshield Network Security appliances

are based on a hardened version of FreeBSD. The BSD license

allows them to integrate their own intellectual property with

the system while returning a great deal of interesting

development to the community.

The Weather

Channel

- The IntelliStar appliance that is installed

at each local cable provider's headend and is responsible

for injecting local weather forecasts into the cable TV

network's programming runs FreeBSD.

Verisign

- Verisign is responsible for operating the

.com and .net root domain registries as well as the

accompanying DNS infrastructure. They rely on a number of

different network operating systems including FreeBSD to

ensure there is no common point of failure in their

infrastructure.

Voxer

- Voxer powers their mobile voice messaging

platform with ZFS on FreeBSD. Voxer switched from a Solaris

derivative to FreeBSD because of its superior documentation,

larger and more active community, and more developer

friendly environment. In addition to critical features

like ZFS and DTrace, FreeBSD also offers

TRIM support for ZFS.

Fudo

Security

- The FUDO security appliance allows

enterprises to monitor, control, record, and audit

contractors and administrators who work on their systems.

Based on all of the best security features of FreeBSD

including ZFS, GELI, Capsicum, HAST, and

auditdistd.

FreeBSD has also spawned a number of related open source

projects:

BSD

Router

- A FreeBSD based replacement for large

enterprise routers designed to run on standard PC

hardware.

FreeNAS

- A customized FreeBSD designed to be used as a

network file server appliance. Provides a python based

web interface to simplify the management of both the UFS

and ZFS file systems. Includes support for NFS, SMB/CIFS,

AFP, FTP, and iSCSI. Includes an extensible plugin system

based on FreeBSD jails.

GhostBSD

- is derived from FreeBSD, uses the GTK

environment to provide a beautiful looks and comfortable

experience on the modern BSD platform offering a natural

and native UNIX® work environment.

mfsBSD

- A toolkit for building a FreeBSD system image

that runs entirely from memory.

NAS4Free

- A file server distribution based on FreeBSD

with a PHP powered web interface.

OPNSense

- OPNsense is an open source, easy-to-use and

easy-to-build FreeBSD based firewall and routing platform.

OPNsense includes most of the features available in

expensive commercial firewalls, and more in many cases.

It brings the rich feature set of commercial offerings

with the benefits of open and verifiable sources.

TrueOS

- TrueOS is based on the legendary security

and stability of FreeBSD. TrueOS follows FreeBSD-CURRENT, with

the latest drivers, security updates, and packages

available.

MidnightBSD

- is a FreeBSD derived operating system

developed with desktop users in mind. It includes all the

software you'd expect for your daily tasks: mail,

web browsing, word processing, gaming, and much

more.

NomadBSD

- is a persistent live system for USB flash

drives, based on FreeBSD. Together with automatic hardware

detection and setup, it is configured to be used as a

desktop system that works out of the box, but can also be

used for data recovery, for educational purposes, or to

test FreeBSD's hardware compatibility.

pfSense

- A firewall distribution based on FreeBSD with

a huge array of features and extensive IPv6

support.

ZRouter

- An open source alternative firmware for

embedded devices based on FreeBSD. Designed to replace the

proprietary firmware on off-the-shelf routers.

A list of

testimonials from companies basing their products and

services on FreeBSD can be found at the FreeBSD

Foundation website. Wikipedia also maintains a list

of products based on FreeBSD.

1.3. About the FreeBSD Project

The following section provides some background information

on the project, including a brief history, project goals, and

the development model of the project.

1.3.1. A Brief History of FreeBSD

The FreeBSD Project had its genesis in the early part

of 1993, partially as the brainchild of the Unofficial

386BSDPatchkit's last 3 coordinators: Nate Williams,

Rod Grimes and Jordan Hubbard.

The original goal was to produce an intermediate snapshot

of 386BSD in order to fix a number of problems that

the patchkit mechanism was just not capable of solving. The

early working title for the project was 386BSD 0.5 or 386BSD

Interim in reference of that fact.

386BSD was Bill Jolitz's operating system, which had been

up to that point suffering rather severely from almost a

year's worth of neglect. As the patchkit swelled ever more

uncomfortably with each passing day, they decided to assist

Bill by providing this interim “cleanup”

snapshot. Those plans came to a rude halt when Bill Jolitz

suddenly decided to withdraw his sanction from the project

without any clear indication of what would be done

instead.

The trio thought that the goal remained worthwhile, even

without Bill's support, and so they adopted the name "FreeBSD"

coined by David Greenman. The initial objectives were set

after consulting with the system's current users and, once it

became clear that the project was on the road to perhaps even

becoming a reality, Jordan contacted Walnut Creek CDROM with

an eye toward improving FreeBSD's distribution channels for those

many unfortunates without easy access to the Internet. Walnut

Creek CDROM not only supported the idea of distributing FreeBSD

on CD but also went so far as to provide the project with a

machine to work on and a fast Internet connection. Without

Walnut Creek CDROM's almost unprecedented degree of faith in

what was, at the time, a completely unknown project, it is

quite unlikely that FreeBSD would have gotten as far, as fast, as

it has today.

The first CD-ROM (and general net-wide) distribution was

FreeBSD 1.0, released in December of 1993. This was based

on the 4.3BSD-Lite (“Net/2”) tape from U.C.

Berkeley, with many components also provided by 386BSD and the

Free Software Foundation. It was a fairly reasonable success

for a first offering, and they followed it with the highly

successful FreeBSD 1.1 release in May of 1994.

Around this time, some rather unexpected storm clouds

formed on the horizon as Novell and U.C. Berkeley settled

their long-running lawsuit over the legal status of the

Berkeley Net/2 tape. A condition of that settlement was U.C.

Berkeley's concession that large parts of Net/2 were

“encumbered” code and the property of Novell, who

had in turn acquired it from AT&T some time previously.

What Berkeley got in return was Novell's

“blessing” that the 4.4BSD-Lite release, when

it was finally released, would be declared unencumbered and

all existing Net/2 users would be strongly encouraged to

switch. This included FreeBSD, and the project was given until

the end of July 1994 to stop shipping its own Net/2 based

product. Under the terms of that agreement, the project was

allowed one last release before the deadline, that release

being FreeBSD 1.1.5.1.

FreeBSD then set about the arduous task of literally

re-inventing itself from a completely new and rather

incomplete set of 4.4BSD-Lite bits. The “Lite”

releases were light in part because Berkeley's CSRG had

removed large chunks of code required for actually

constructing a bootable running system (due to various legal

requirements) and the fact that the Intel port of 4.4 was

highly incomplete. It took the project until November of 1994

to make this transition, and in December it released

FreeBSD 2.0 to the world. Despite being still more than a

little rough around the edges, the release was a significant

success and was followed by the more robust and easier to

install FreeBSD 2.0.5 release in June of 1995.

Since that time, FreeBSD has made a series of releases each

time improving the stability, speed, and feature set of the

previous version.

For now, long-term development projects continue to take

place in the 10.X-CURRENT (trunk) branch, and snapshot

releases of 10.X are continually made available from the

snapshot server as work progresses.

1.3.2. FreeBSD Project Goals

Contributed by Jordan Hubbard.

The goals of the FreeBSD Project are to provide software

that may be used for any purpose and without strings attached.

Many of us have a significant investment in the code (and

project) and would certainly not mind a little financial

compensation now and then, but we are definitely not prepared

to insist on it. We believe that our first and foremost

“mission” is to provide code to any and all

comers, and for whatever purpose, so that the code gets the

widest possible use and provides the widest possible benefit.

This is, I believe, one of the most fundamental goals of Free

Software and one that we enthusiastically support.

That code in our source tree which falls under the GNU

General Public License (GPL) or Library General Public License

(LGPL) comes with slightly more strings attached, though at

least on the side of enforced access rather than the usual

opposite. Due to the additional complexities that can evolve

in the commercial use of GPL software we do, however, prefer

software submitted under the more relaxed BSD license when

it is a reasonable option to do so.

1.3.3. The FreeBSD Development Model

Contributed by Satoshi Asami.

The development of FreeBSD is a very open and flexible

process, being literally built from the contributions of

thousands of people around the world, as can be seen from our

list

of contributors. FreeBSD's development infrastructure

allow these thousands of contributors to collaborate over the

Internet. We are constantly on the lookout for new developers

and ideas, and those interested in becoming more closely

involved with the project need simply contact us at the

FreeBSD technical discussions mailing list. The FreeBSD announcements mailing list is also available to those

wishing to make other FreeBSD users aware of major areas of

work.

Useful things to know about the FreeBSD Project and its

development process, whether working independently or in close

cooperation:

- The SVN repositories

For several years, the central source tree for FreeBSD

was maintained by

CVS

(Concurrent Versions System), a freely available source

code control tool. In June 2008, the Project switched

to using SVN

(Subversion). The switch was deemed necessary, as the

technical limitations imposed by

CVS were becoming obvious due

to the rapid expansion of the source tree and the amount

of history already stored. The Documentation Project

and Ports Collection repositories also moved from

CVS to

SVN in May 2012 and July

2012, respectively. Please refer to the Obtaining the Source

section for more information on obtaining the

FreeBSD src/ repository and Using the Ports

Collection for details on obtaining the FreeBSD

Ports Collection.

- The committers list

The committers

are the people who have

write access to the Subversion

tree, and are authorized to make modifications to the

FreeBSD source (the term “committer” comes

from commit, the source control

command which is used to bring new changes into the

repository). Anyone can submit a bug to the Bug

Database. Before submitting a bug report, the

FreeBSD mailing lists, IRC channels, or forums can be used to

help verify that an issue is actually a bug.

- The FreeBSD core team

The FreeBSD core team

would be equivalent to the board of

directors if the FreeBSD Project were a company. The

primary task of the core team is to make sure the

project, as a whole, is in good shape and is heading in

the right directions. Inviting dedicated and

responsible developers to join our group of committers

is one of the functions of the core team, as is the

recruitment of new core team members as others move on.

The current core team was elected from a pool of

committer candidates in June 2020. Elections are held

every 2 years.

Note:

Like most developers, most members of the

core team are also volunteers when

it comes to FreeBSD development and do not benefit from

the project financially, so “commitment”

should also not be misconstrued as meaning

“guaranteed support.” The

“board of directors” analogy above is not

very accurate, and it may be more suitable to say that

these are the people who gave up their lives in favor

of FreeBSD against their better judgement!

- Outside contributors

Last, but definitely not least, the largest group of

developers are the users themselves who provide feedback

and bug fixes to us on an almost constant basis. The

primary way of keeping in touch with FreeBSD's more

non-centralized development is to subscribe to the

FreeBSD technical discussions mailing list where such things are discussed. See

Appendix C, Resources on the Internet for more information about

the various FreeBSD mailing lists.

The

FreeBSD Contributors List

is a long and growing one, so why not join

it by contributing something back to FreeBSD today?

Providing code is not the only way of contributing

to the project; for a more complete list of things that

need doing, please refer to the FreeBSD Project

web site.

In summary, our development model is organized as a loose

set of concentric circles. The centralized model is designed

for the convenience of the users of FreeBSD,

who are provided with an easy way of tracking one central code

base, not to keep potential contributors out! Our desire is to

present a stable operating system with a large set of coherent

application programs that the

users can easily install and use — this model works very

well in accomplishing that.

All we ask of those who would join us as FreeBSD developers

is some of the same dedication its current people have to its

continued success!

1.3.4. Third Party Programs

In addition to the base distributions, FreeBSD offers a

ported software collection with thousands of commonly

sought-after programs. At the time of this writing, there

were over 24,000 ports! The list of ports ranges from

http servers, to games, languages, editors, and almost

everything in between. The entire Ports Collection requires

approximately 500 MB. To compile a port, you simply

change to the directory of the program you wish to install,

type make install, and let the system do

the rest. The full original distribution for each port you

build is retrieved dynamically so you need only enough disk

space to build the ports you want. Almost every port is also

provided as a pre-compiled “package”, which can

be installed with a simple command

(pkg install) by those who do not wish to

compile their own ports from source. More information on

packages and ports can be found in

Chapter 4, Installing Applications: Packages and Ports.

1.3.5. Additional Documentation

All supported FreeBSD versions provide an option in the

installer to

install additional documentation under

/usr/local/share/doc/freebsd during the

initial system setup. Documentation may also be installed at

any later time using packages as described in

Section 24.3.2, “Updating Documentation from Ports”. You may view the

locally installed manuals with any HTML capable browser using

the following URLs:

You can also view the master (and most frequently updated)

copies at https://www.FreeBSD.org/.

Chapter 2. Installing FreeBSD

Restructured, reorganized, and parts rewritten

by Jim Mock.

Updated for bsdinstall by Gavin Atkinson and Warren Block.

Updated for root-on-ZFS by Allan Jude.

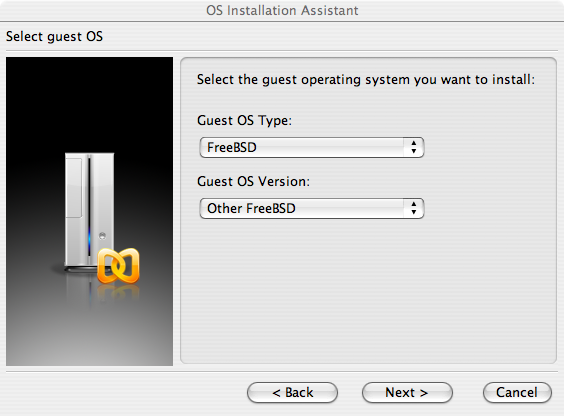

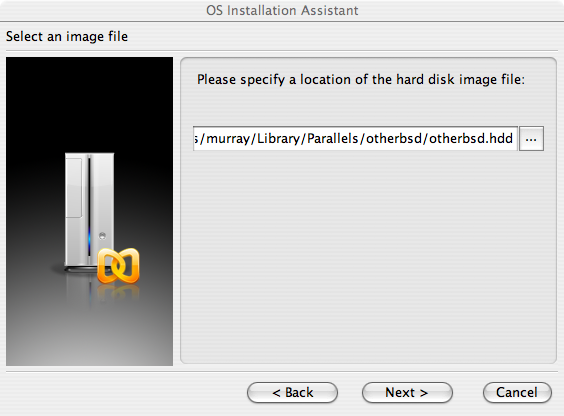

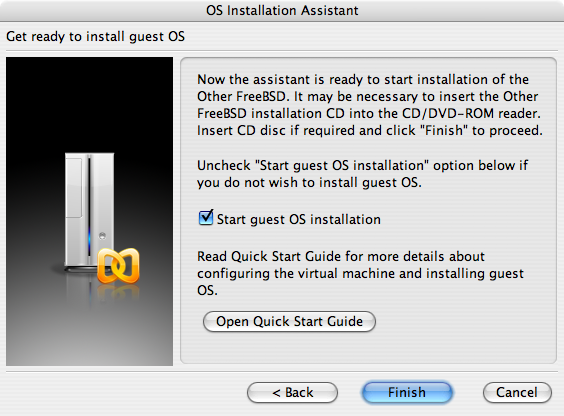

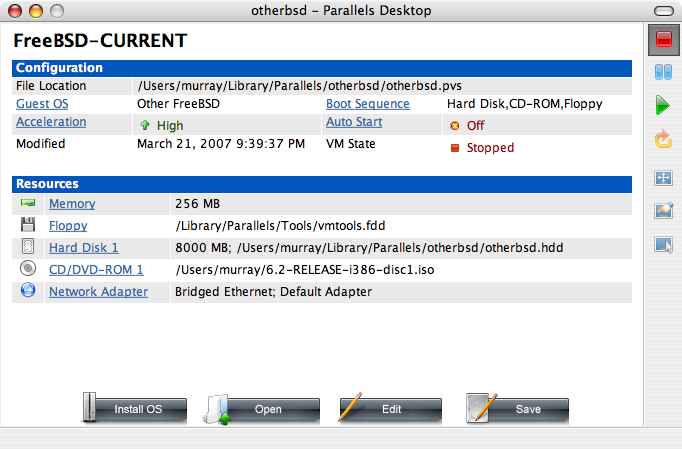

There are several different ways of getting FreeBSD to run,

depending on the environment. Those are:

Virtual Machine images, to download and import on a

virtual environment of choice. These can be downloaded from

the Download

FreeBSD page. There are images for KVM

(“qcow2”), VMWare (“vmdk”),

Hyper-V (“vhd”), and raw device images that are

universally supported. These are not installation images,

but rather the preconfigured (“already

installed”) instances, ready to run and perform

post-installation tasks.

Virtual Machine images available at Amazon's AWS

Marketplace, Microsoft

Azure Marketplace, and Google

Cloud Platform, to run on their respective hosting

services. For more information on deploying FreeBSD on Azure

please consult the relevant chapter in the Azure

Documentation.

SD card images, for embedded systems such as Raspberry

Pi or BeagleBone Black. These can be downloaded from the

Download

FreeBSD page. These files must be uncompressed and

written as a raw image to an SD card, from which the board

will then boot.

Installation images, to install FreeBSD on

a hard drive for the usual desktop, laptop, or server

systems.

The rest of this chapter describes the fourth case,

explaining how to install FreeBSD using the text-based

installation program named

bsdinstall.

In general, the installation instructions in this chapter

are written for the i386™ and AMD64

architectures. Where applicable, instructions specific to other

platforms will be listed. There may be minor differences

between the installer and what is shown here, so use this

chapter as a general guide rather than as a set of literal

instructions.

After reading this chapter, you will know:

The minimum hardware requirements and FreeBSD supported

architectures.

How to create the FreeBSD installation media.

How to start

bsdinstall.

The questions bsdinstall will

ask, what they mean, and how to answer them.

How to troubleshoot a failed installation.

How to access a live version of FreeBSD before committing

to an installation.

Before reading this chapter, you should:

2.2. Minimum Hardware Requirements

The hardware requirements to install FreeBSD vary by

architecture. Hardware architectures and devices supported by a

FreeBSD release are listed on the FreeBSD Release

Information page. The FreeBSD download page

also has recommendations for choosing the correct image for

different architectures.

A FreeBSD installation requires a minimum of 96 MB of

RAM and 1.5 GB of free hard drive space.

However, such small amounts of memory and disk space are really

only suitable for custom applications like embedded appliances.

General-purpose desktop systems need more resources.

2-4 GB RAM and at least 8 GB hard drive space is a

good starting point.

These are the processor requirements for each

architecture:

- amd64

This is the most common desktop and laptop processor

type, used in most modern systems. Intel® calls it

Intel64. Other manufacturers sometimes

call it x86-64.

Examples of amd64 compatible processors

include: AMD Athlon™64, AMD Opteron™,

multi-core Intel® Xeon™, and

Intel® Core™ 2 and later processors.

- i386

Older desktops and laptops often use this 32-bit, x86

architecture.

Almost all i386-compatible processors with a floating

point unit are supported. All Intel® processors 486 or

higher are supported.

FreeBSD will take advantage of Physical Address

Extensions (PAE) support on

CPUs with this feature. A kernel with

the PAE feature enabled will detect

memory above 4 GB and allow it to be used by the

system. However, using PAE places

constraints on device drivers and other features of

FreeBSD.

- powerpc

All New World ROM Apple®

Mac® systems with built-in USB

are supported. SMP is supported on

machines with multiple CPUs.

A 32-bit kernel can only use the first 2 GB of

RAM.

- sparc64

Systems supported by FreeBSD/sparc64 are listed at

the FreeBSD/sparc64

Project.

SMP is supported on all systems

with more than 1 processor. A dedicated disk is required

as it is not possible to share a disk with another

operating system at this time.

2.3. Pre-Installation Tasks

Once it has been determined that the system meets the

minimum hardware requirements for installing FreeBSD, the

installation file should be downloaded and the installation

media prepared. Before doing this, check that the system is

ready for an installation by verifying the items in this

checklist:

Back Up Important Data

Before installing any operating system,

always backup all important data first.

Do not store the backup on the system being installed.

Instead, save the data to a removable disk such as a

USB drive, another system on the network,

or an online backup service. Test the backup before

starting the installation to make sure it contains all of

the needed files. Once the installer formats the system's

disk, all data stored on that disk will be lost.

Decide Where to Install FreeBSD

If FreeBSD will be the only operating system installed,

this step can be skipped. But if FreeBSD will share the disk

with another operating system, decide which disk or

partition will be used for FreeBSD.

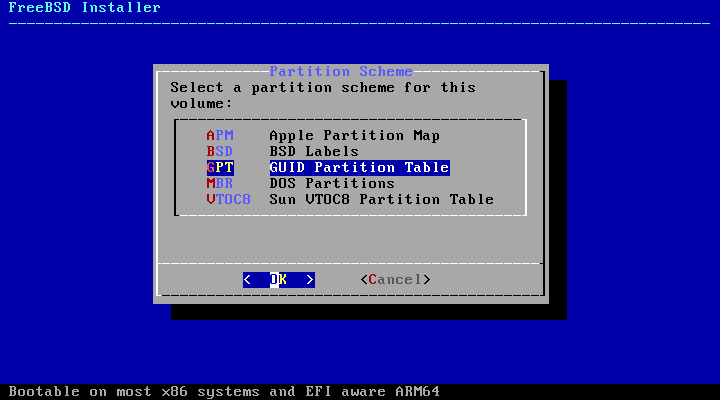

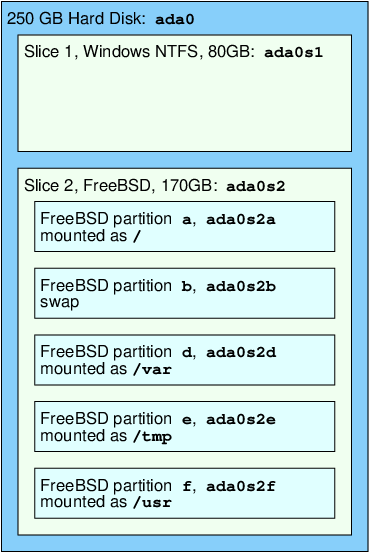

In the i386 and amd64 architectures, disks

can be divided into multiple partitions using one of two

partitioning schemes. A traditional Master Boot

Record (MBR) holds a

partition table defining up to four primary

partitions. For historical reasons, FreeBSD

calls these primary partition

slices. One of these primary

partitions can be made into an extended

partition containing multiple

logical partitions. The

GUID Partition Table

(GPT) is a newer and simpler method of

partitioning a disk. Common GPT

implementations allow up to 128 partitions per disk,

eliminating the need for logical partitions.

The FreeBSD boot loader requires either a primary or

GPT partition. If all of the primary or

GPT partitions are already in use, one

must be freed for FreeBSD. To create a partition without

deleting existing data, use a partition resizing tool to

shrink an existing partition and create a new partition

using the freed space.

A variety of free and commercial partition resizing

tools are listed at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_disk_partitioning_software.

GParted Live (http://gparted.sourceforge.net/livecd.php)

is a free live CD which includes the

GParted partition editor.

GParted is also included with

many other Linux live CD

distributions.

Warning:

When used properly, disk shrinking utilities can

safely create space for creating a new partition. Since

the possibility of selecting the wrong partition exists,

always backup any important data and verify the integrity

of the backup before modifying disk partitions.

Disk partitions containing different operating systems

make it possible to install multiple operating systems on

one computer. An alternative is to use virtualization

(Chapter 22, Virtualization) which allows multiple

operating systems to run at the same time without modifying

any disk partitions.

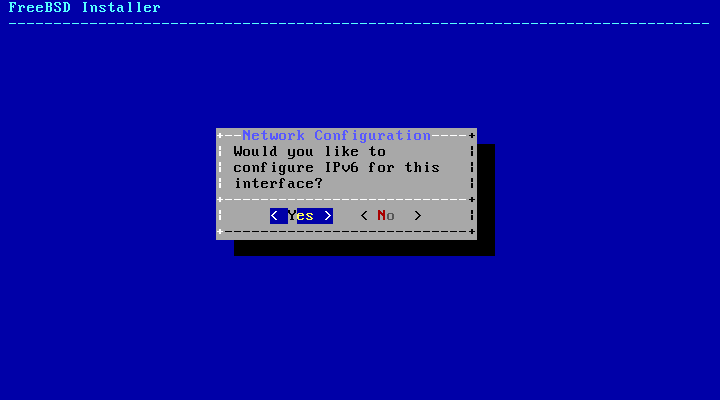

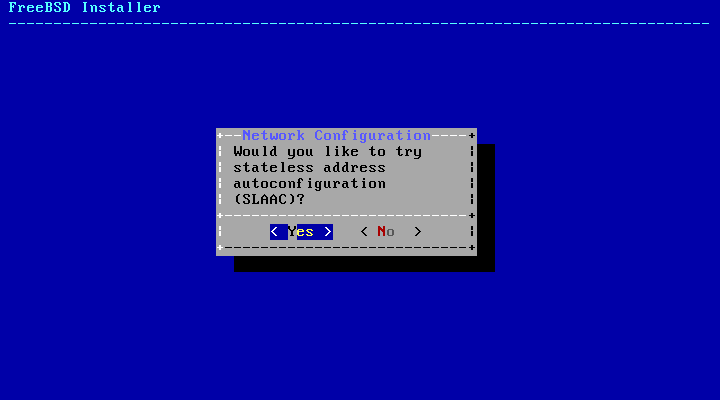

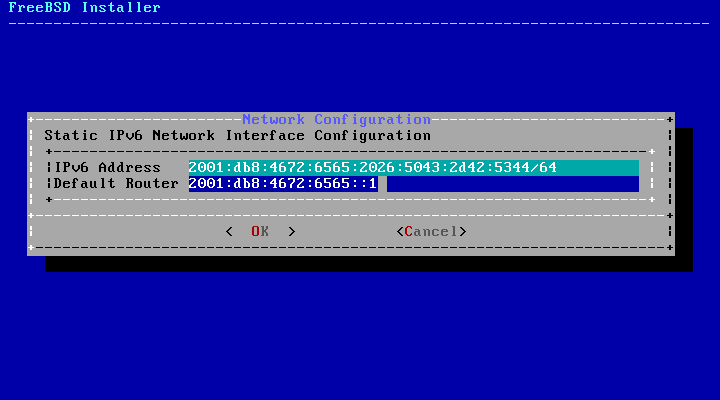

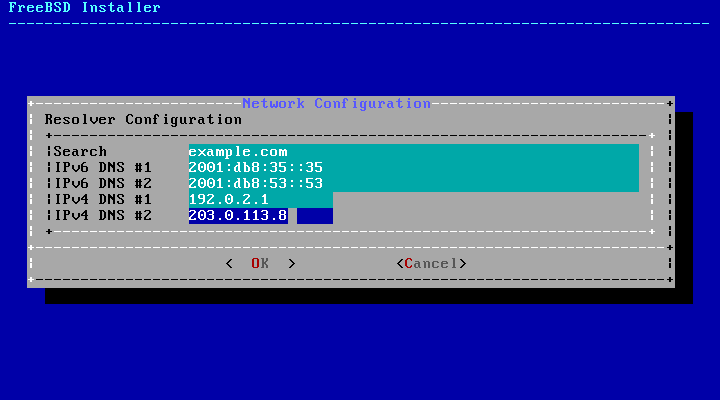

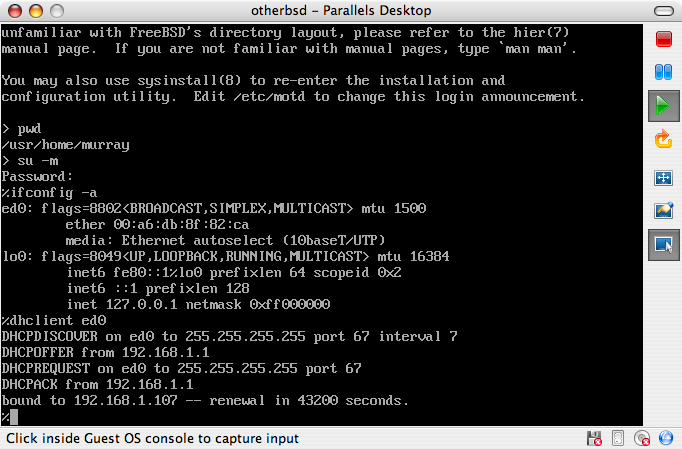

Collect Network Information

Some FreeBSD installation methods require a network

connection in order to download the installation files.

After any installation, the installer will offer to setup

the system's network interfaces.

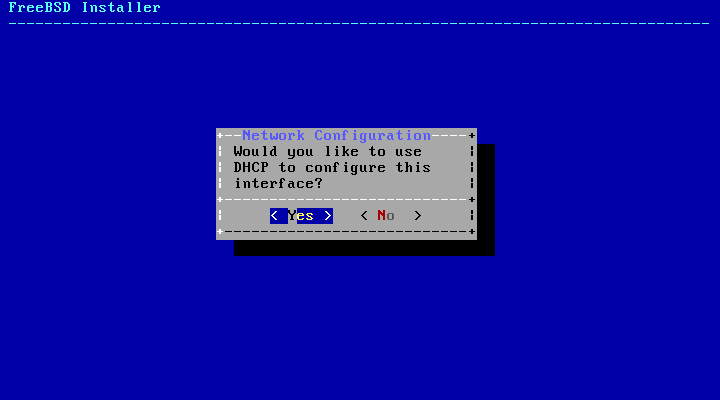

If the network has a DHCP server, it

can be used to provide automatic network configuration. If

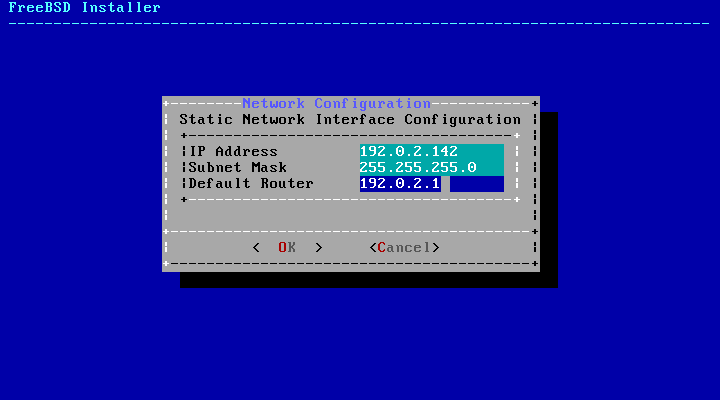

DHCP is not available, the following

network information for the system must be obtained from the

local network administrator or Internet service

provider:

Required Network Information

IP address

Subnet mask

IP address of default

gateway

Domain name of the network

IP addresses of the network's

DNS servers

Check for FreeBSD Errata

Although the FreeBSD Project strives to ensure that

each release of FreeBSD is as stable as possible, bugs

occasionally creep into the process. On very rare occasions

those bugs affect the installation process. As these

problems are discovered and fixed, they are noted in the

FreeBSD Errata (https://www.freebsd.org/releases/12.1R/errata.html)

on the FreeBSD web site. Check the errata before installing to

make sure that there are no problems that might affect the

installation.

Information and errata for all the releases can be found

on the release information section of the FreeBSD web site

(https://www.freebsd.org/releases/index.html).

2.3.1. Prepare the Installation Media

The FreeBSD installer is not an application that can be run

from within another operating system. Instead, download a

FreeBSD installation file, burn it to the media associated with

its file type and size (CD,

DVD, or USB), and boot

the system to install from the inserted media.

FreeBSD installation files are available at www.freebsd.org/where.html#download.

Each installation file's name includes the release version of

FreeBSD, the architecture, and the type of file. For example, to

install FreeBSD 12.1 on an amd64 system from a

DVD, download

FreeBSD-12.1-RELEASE-amd64-dvd1.iso, burn

this file to a DVD, and boot the system

with the DVD inserted.

Installation files are available in several formats.

The formats vary depending on computer architecture and media

type.

Additional

installation files are included for computers that boot with

UEFI (Unified Extensible Firmware

Interface). The names of these files include the string

uefi.

File types:

-bootonly.iso: This is the smallest

installation file as it only contains the installer. A

working Internet connection is required during

installation as the installer will download the files it

needs to complete the FreeBSD installation. This file should

be burned to a CD using a

CD burning application.

-disc1.iso: This file contains all

of the files needed to install FreeBSD, its source, and the

Ports Collection. It should be burned to a

CD using a CD

burning application.

-dvd1.iso: This file contains all

of the files needed to install FreeBSD, its source, and the

Ports Collection. It also contains a set of popular

binary packages for installing a window manager and some

applications so that a complete system can be installed

from media without requiring a connection to the Internet.

This file should be burned to a DVD

using a DVD burning application.

-memstick.img: This file contains

all of the files needed to install FreeBSD, its source, and

the Ports Collection. It should be burned to a

USB stick using the instructions

below.

-mini-memstick.img: Like

-bootonly.iso, does not include

installation files, but downloads them as needed. A

working internet connection is required during

installation. Write this file to a USB

stick as shown in Section 2.3.1.1, “Writing an Image File to USB”.

After downloading the image file, download

CHECKSUM.SHA256 from

the same directory. Calculate a

checksum for the image file.

FreeBSD provides sha256(1) for this, used as sha256

imagefilename.

Other operating systems have similar programs.

Compare the calculated checksum with the one shown in

CHECKSUM.SHA256. The checksums must

match exactly. If the checksums do not match, the image file

is corrupt and must be downloaded again.

2.3.1.1. Writing an Image File to USB

The *.img file is an

image of the complete contents of a

memory stick. It cannot be copied to

the target device as a file. Several applications are

available for writing the *.img to a

USB stick. This section describes two of

these utilities.

Important:

Before proceeding, back up any important data on the

USB stick. This procedure will erase

the existing data on the stick.

Procedure 2.1. Using dd to Write the

Image

Warning:

This example uses /dev/da0 as

the target device where the image will be written. Be

very careful that the correct

device is used as this command will destroy the existing

data on the specified target device.

The dd(1) command-line utility is

available on BSD, Linux®, and Mac OS® systems. To burn

the image using dd, insert the

USB stick and determine its device

name. Then, specify the name of the downloaded

installation file and the device name for the

USB stick. This example burns the

amd64 installation image to the first

USB device on an existing FreeBSD

system.

# dd if=FreeBSD-12.1-RELEASE-amd64-memstick.img of=/dev/da0 bs=1M conv=sync

If this command fails, verify that the

USB stick is not mounted and that the

device name is for the disk, not a partition. Some

operating systems might require this command to be run

with sudo(8). The dd(1) syntax varies slightly

across different platforms; for example, Mac OS® requires

a lower-case bs=1m.

Systems like Linux® might buffer

writes. To force all writes to complete, use

sync(8).

Procedure 2.2. Using Windows® to Write the Image

Warning:

Be sure to give the correct drive letter as the

existing data on the specified drive will be overwritten

and destroyed.

Obtaining Image Writer for

Windows®

Image Writer for

Windows® is a free application that can

correctly write an image file to a memory stick.

Download it from https://sourceforge.net/projects/win32diskimager/

and extract it into a folder.

Writing the Image with Image Writer

Double-click the

Win32DiskImager icon to start

the program. Verify that the drive letter shown under

Device is the drive

with the memory stick. Click the folder icon and select

the image to be written to the memory stick. Click

[ Save ] to accept the

image file name. Verify that everything is correct, and

that no folders on the memory stick are open in other

windows. When everything is ready, click

[ Write ] to write the

image file to the memory stick.

You are now ready to start installing FreeBSD.

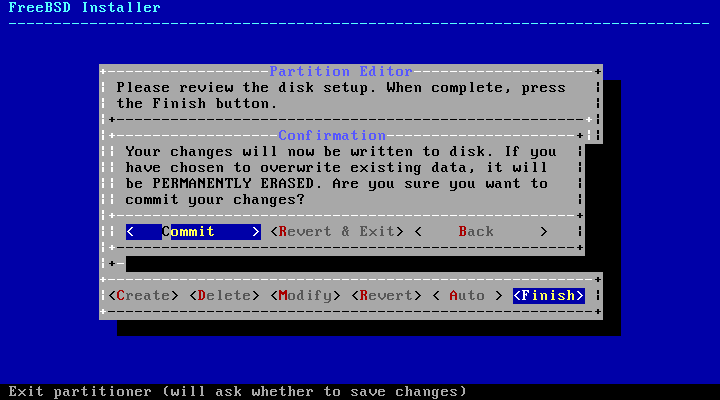

2.4. Starting the Installation

Important:

By default, the installation will not make any changes to

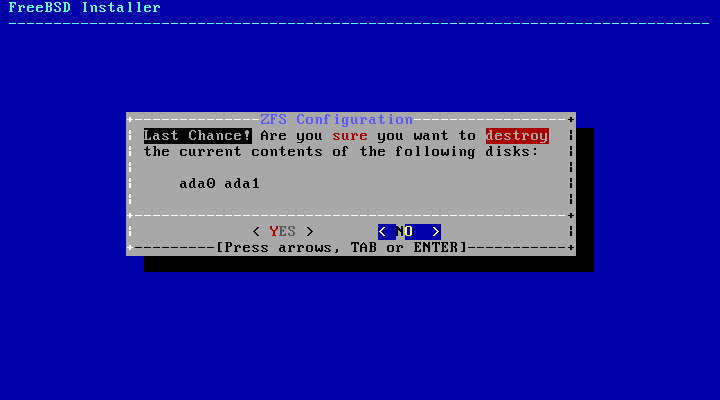

the disk(s) before the following message:

Your changes will now be written to disk. If you

have chosen to overwrite existing data, it will

be PERMANENTLY ERASED. Are you sure you want to

commit your changes?

The install can be exited at any time prior to this

warning. If

there is a concern that something is incorrectly configured,

just turn the computer off before this point and no changes

will be made to the system's disks.

This section describes how to boot the system from the

installation media which was prepared using the instructions in

Section 2.3.1, “Prepare the Installation Media”. When using a

bootable USB stick, plug in the USB stick

before turning on the computer. When booting from

CD or DVD, turn on the

computer and insert the media at the first opportunity. How to

configure the system to boot from the inserted media depends

upon the architecture.

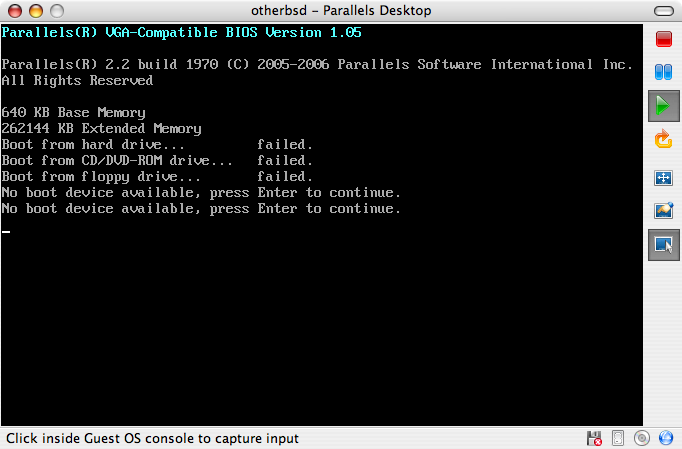

2.4.1. Booting on i386™ and amd64

These architectures provide a BIOS

menu for selecting the boot device. Depending upon the

installation media being used, select the

CD/DVD or

USB device as the first boot device. Most

systems also provide a key for selecting the boot device

during startup without having to enter the

BIOS. Typically, the key is either

F10, F11,

F12, or Escape.

If the computer loads the existing operating system

instead of the FreeBSD installer, then either:

The installation media was not inserted early enough

in the boot process. Leave the media inserted and try

restarting the computer.

The BIOS changes were incorrect or

not saved. Double-check that the right boot device is

selected as the first boot device.

This system is too old to support booting from the

chosen media. In this case, the Plop Boot

Manager (http://www.plop.at/en/bootmanagers.html)

can be used to boot the system from the selected

media.

2.4.2. Booting on PowerPC®

On most machines, holding C on the

keyboard during boot will boot from the CD.

Otherwise, hold Command+Option+O+F, or

Windows+Alt+O+F on non-Apple® keyboards. At the

0 > prompt, enter

boot cd:,\ppc\loader cd:0

Once the system boots from the installation media, a menu

similar to the following will be displayed:

By default, the menu will wait ten seconds for user input

before booting into the FreeBSD installer or, if FreeBSD is already

installed, before booting into FreeBSD. To pause the boot timer

in order to review the selections, press

Space. To select an option, press its

highlighted number, character, or key. The following options

are available.

Boot Multi User: This will

continue the FreeBSD boot process. If the boot timer has

been paused, press 1, upper- or

lower-case B, or

Enter.

Boot Single User: This mode can be

used to fix an existing FreeBSD installation as described in

Section 13.2.4.1, “Single-User Mode”. Press

2 or the upper- or lower-case

S to enter this mode.

Escape to loader prompt: This will

boot the system into a repair prompt that contains a

limited number of low-level commands. This prompt is

described in Section 13.2.3, “Stage Three”. Press

3 or Esc to boot into

this prompt.

Reboot: Reboots the system.

Kernel: Loads a different

kernel.

Configure Boot Options: Opens the

menu shown in, and described under, Figure 2.2, “FreeBSD Boot Options Menu”.

The boot options menu is divided into two sections. The

first section can be used to either return to the main boot

menu or to reset any toggled options back to their

defaults.

The next section is used to toggle the available options

to On or Off by pressing

the option's highlighted number or character. The system will

always boot using the settings for these options until they

are modified. Several options can be toggled using this

menu:

ACPI Support: If the system hangs

during boot, try toggling this option to

Off.

Safe Mode: If the system still

hangs during boot even with ACPI

Support set to Off, try

setting this option to On.

Single User: Toggle this option to

On to fix an existing FreeBSD installation

as described in Section 13.2.4.1, “Single-User Mode”. Once

the problem is fixed, set it back to

Off.

Verbose: Toggle this option to

On to see more detailed messages during

the boot process. This can be useful when troubleshooting

a piece of hardware.

After making the needed selections, press

1 or Backspace to return to

the main boot menu, then press Enter to

continue booting into FreeBSD. A series of boot messages will

appear as FreeBSD carries out its hardware device probes and

loads the installation program. Once the boot is complete,

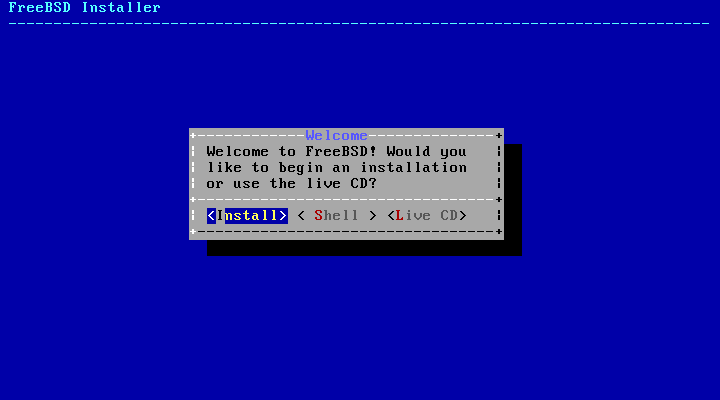

the welcome menu shown in Figure 2.3, “Welcome Menu” will be displayed.

Press Enter to select the default of

[ Install ] to enter the

installer. The rest of this chapter describes how to use this

installer. Otherwise, use the right or left arrows or the

colorized letter to select the desired menu item. The

[ Shell ] can be used to

access a FreeBSD shell in order to use command line utilities to

prepare the disks before installation. The

[ Live CD ] option can be

used to try out FreeBSD before installing it. The live version

is described in Section 2.11, “Using the Live CD”.

Tip:

To review the boot messages, including the hardware

device probe, press the upper- or lower-case

S and then Enter to access

a shell. At the shell prompt, type more

/var/run/dmesg.boot and use the space bar to

scroll through the messages. When finished, type

exit to return to the welcome

menu.

This section shows the order of the

bsdinstall menus and the type of

information that will be asked before the system is installed.

Use the arrow keys to highlight a menu option, then

Space to select or deselect that menu item.

When finished, press Enter to save the

selection and move onto the next screen.

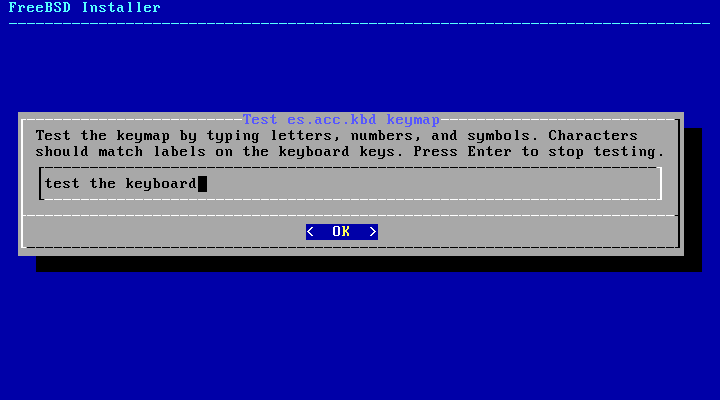

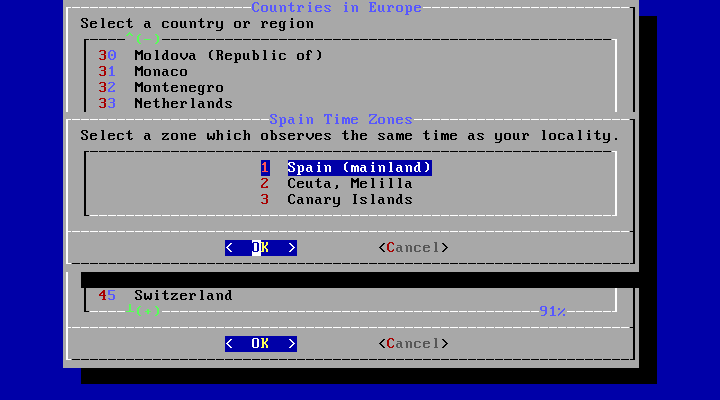

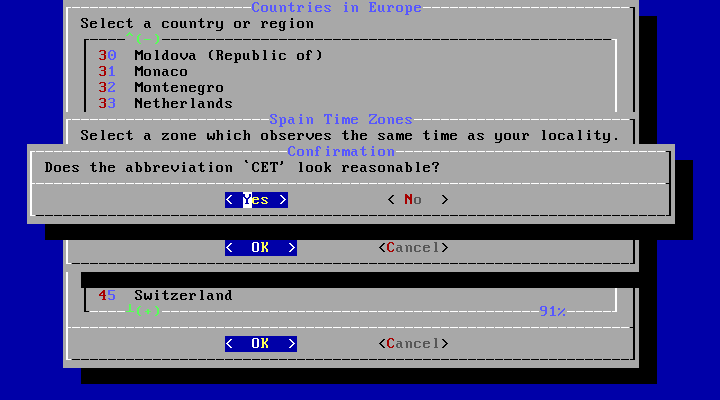

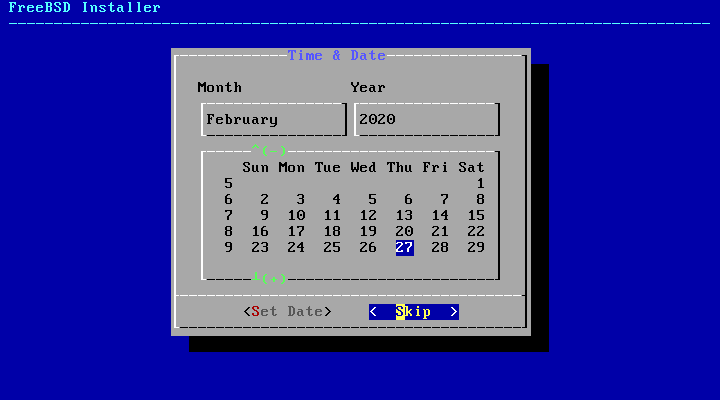

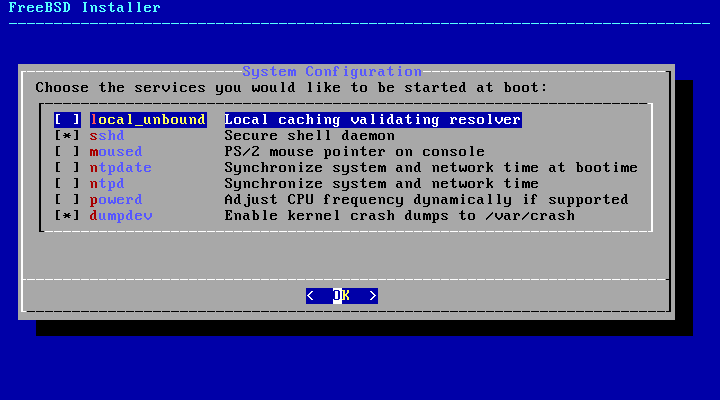

2.5.1. Selecting the Keymap Menu

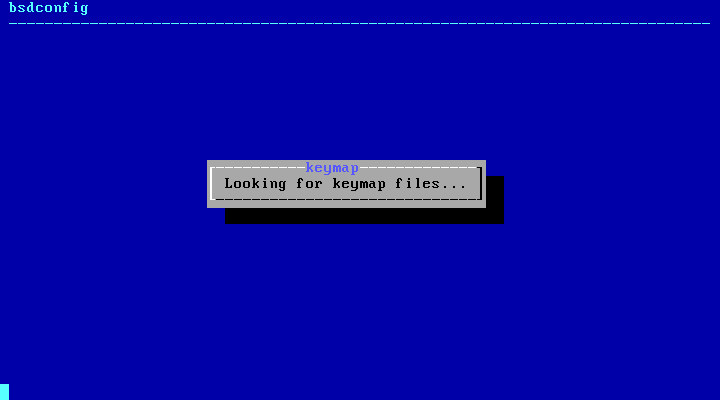

Before starting the process,

bsdinstall will load the keymap

files as show in Figure 2.4, “Keymap Loading”.

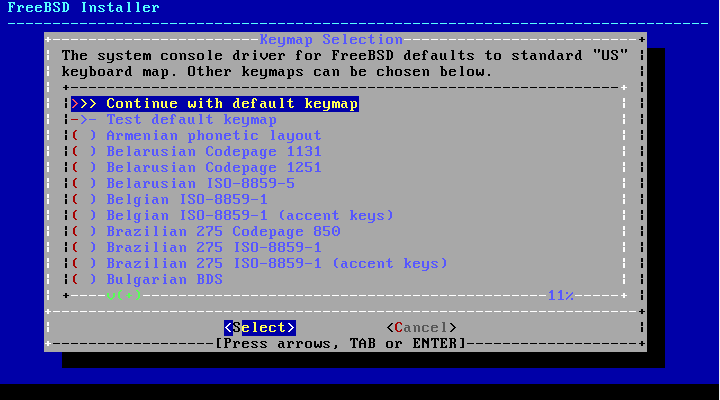

After the keymaps have been loaded

bsdinstall displays the

menu shown in Figure 2.5, “Keymap Selection Menu”. Use the

up and down arrows to select the keymap that most closely

represents the mapping of the keyboard attached to the system.

Press Enter to save the selection.

Note:

Pressing Esc will exit this menu

and use the default keymap. If the choice of keymap is not

clear, is also a safe option.

In addition, when selecting a different keymap, the user

can try the keymap and ensure it is correct before proceeding

as shown in Figure 2.6, “Keymap Testing Menu”.

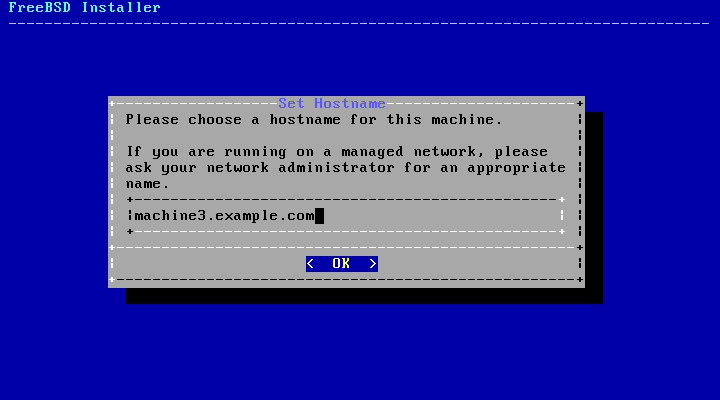

2.5.2. Setting the Hostname

The next bsdinstall menu is

used to set the hostname for the newly installed

system.

Type in a hostname that is unique for the network. It

should be a fully-qualified hostname, such as machine3.example.com.

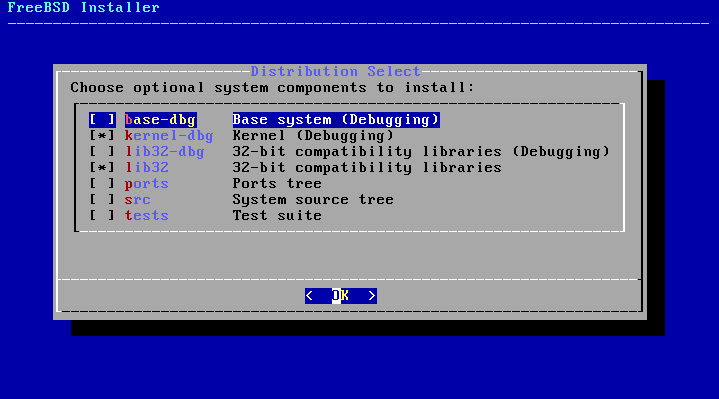

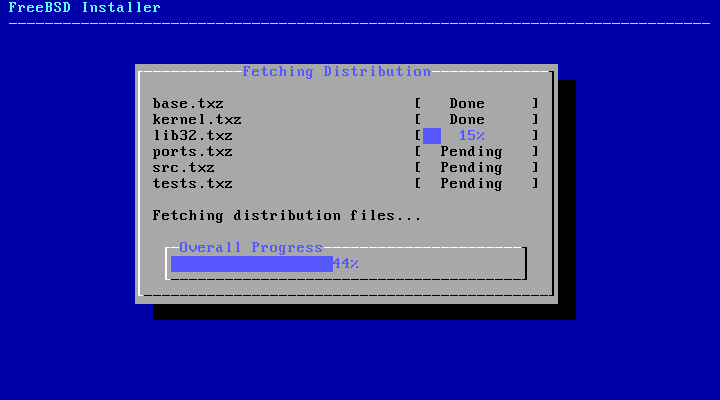

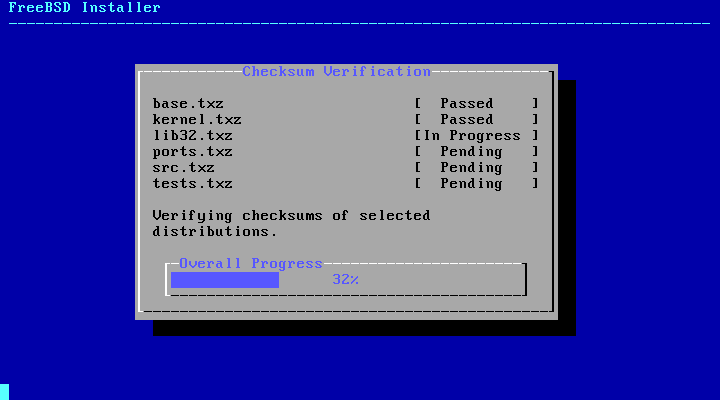

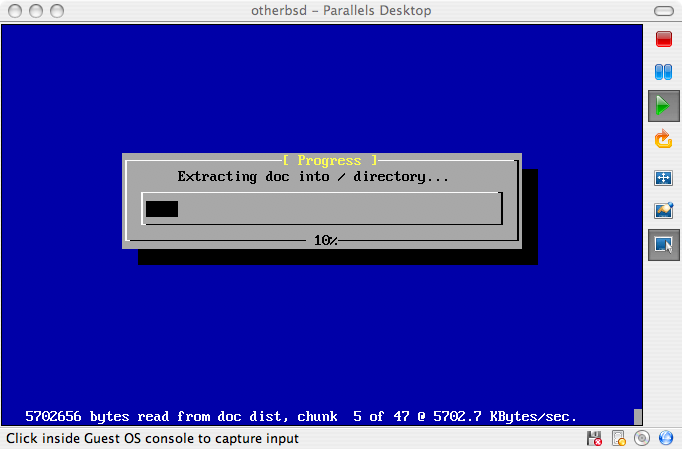

2.5.3. Selecting Components to Install

Next, bsdinstall will prompt to

select optional components to install.

Deciding which components to install will depend largely

on the intended use of the system and the amount of disk space

available. The FreeBSD kernel and userland, collectively known

as the base system, are always

installed. Depending on the architecture, some of these

components may not appear:

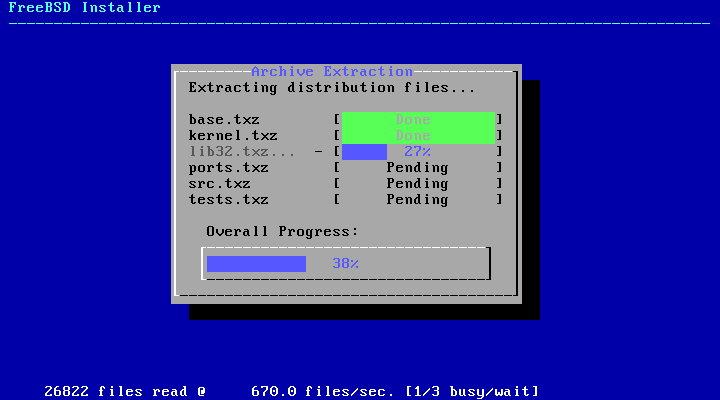

base-dbg - Base tools like

cat,

ls among many others with

debug symbols activated.

kernel-dbg - Kernel and modules with

debug symbols activated.

lib32-dbg - Compatibility libraries

for running 32-bit applications on a 64-bit version of

FreeBSD with debug symbols activated.

lib32 - Compatibility libraries for

running 32-bit applications on a 64-bit version of

FreeBSD.

ports - The FreeBSD Ports Collection

is a collection of files which automates the downloading,

compiling and installation of third-party software

packages. Chapter 4, Installing Applications: Packages and Ports discusses how to use

the Ports Collection.

Warning:

The installation program does not check for

adequate disk space. Select this option only if

sufficient hard disk space is available. The FreeBSD Ports

Collection takes up about 500 MB of disk

space.

src - The complete FreeBSD source code

for both the kernel and the userland. Although not

required for the majority of applications, it may be

required to build device drivers, kernel modules, or some

applications from the Ports Collection. It is also used

for developing FreeBSD itself. The full source tree requires

1 GB of disk space and recompiling the entire FreeBSD

system requires an additional 5 GB of space.

tests - FreeBSD Test Suite.

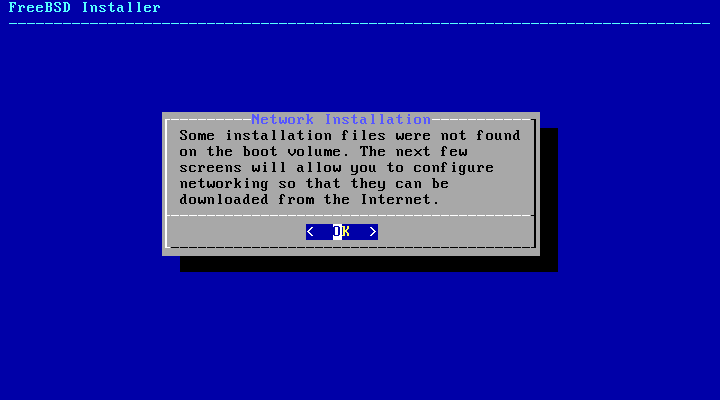

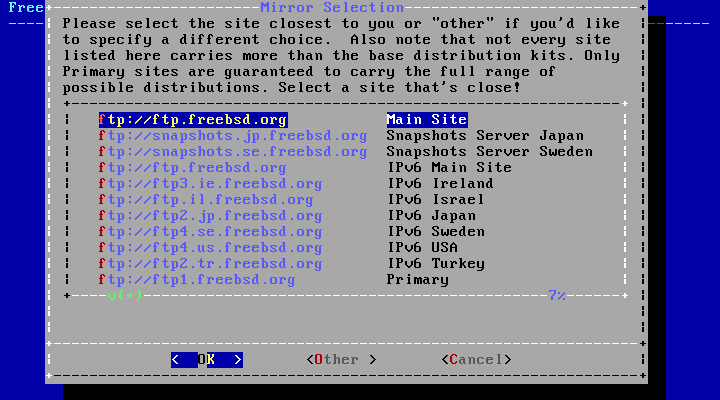

2.5.4. Installing from the Network

The menu shown in

Figure 2.9, “Installing from the Network” only appears

when installing from a -bootonly.iso or

-mini-memstick.img as this installation

media does not hold copies of the installation files.

Since the installation files must be retrieved over a network

connection, this menu indicates that the network interface must

be configured first. If this menu is shown in any step of the

process remember to follow the instructions in

Section 2.9.1, “Configuring Network Interfaces”.

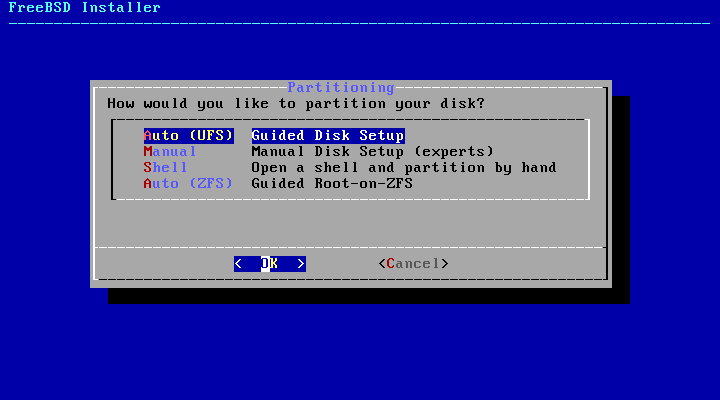

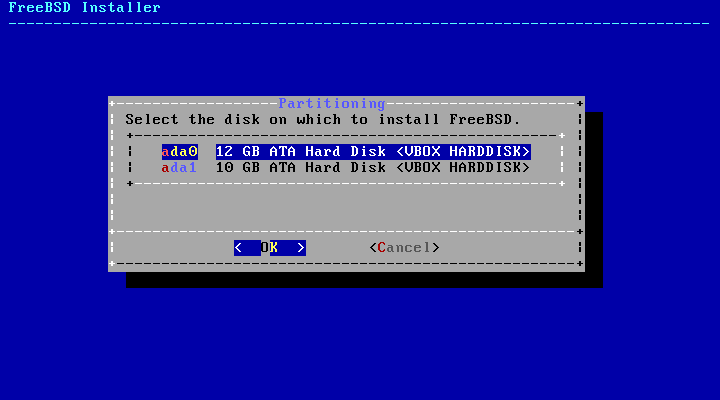

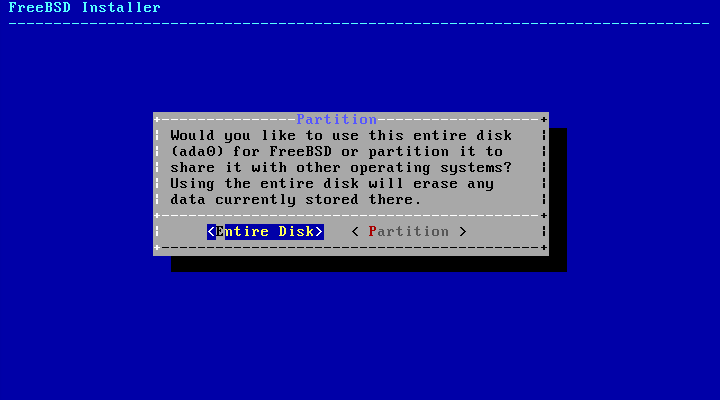

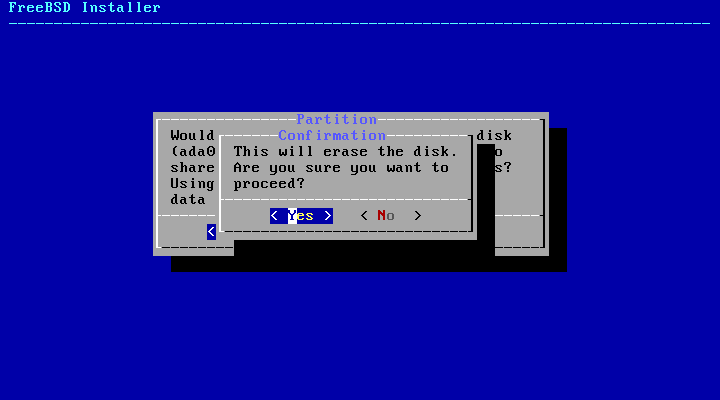

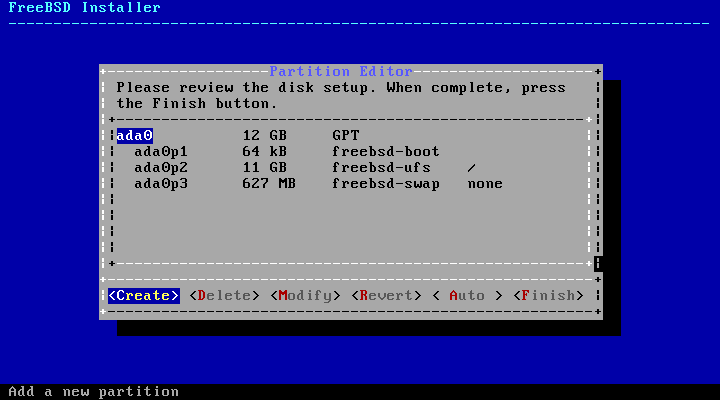

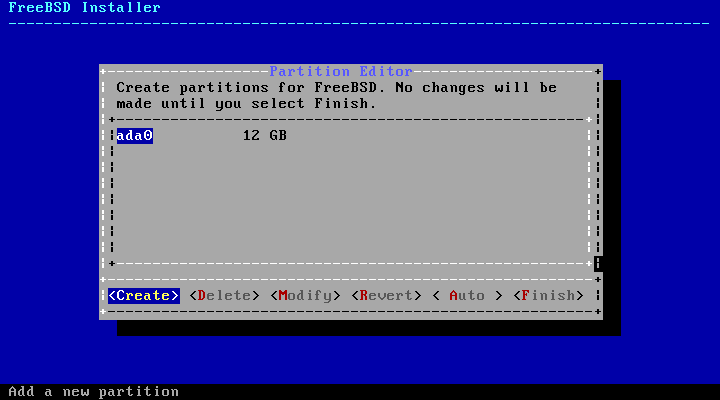

2.6. Allocating Disk Space

The next menu is used to determine the method for

allocating disk space.

bsdinstall gives the user four

methods for allocating disk space:

Auto (UFS) partitioning

automatically sets up the disk partitions using the

UFS file system.

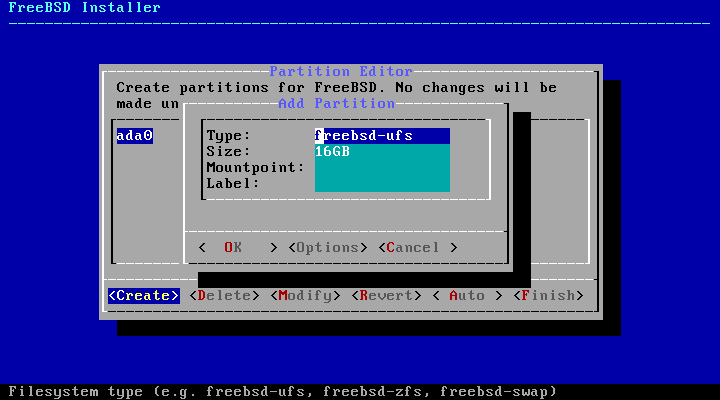

Manual partitioning allows

advanced users to create customized partitions from menu

options.

Shell opens a shell prompt where

advanced users can create customized partitions using

command-line utilities like gpart(8), fdisk(8),

and bsdlabel(8).

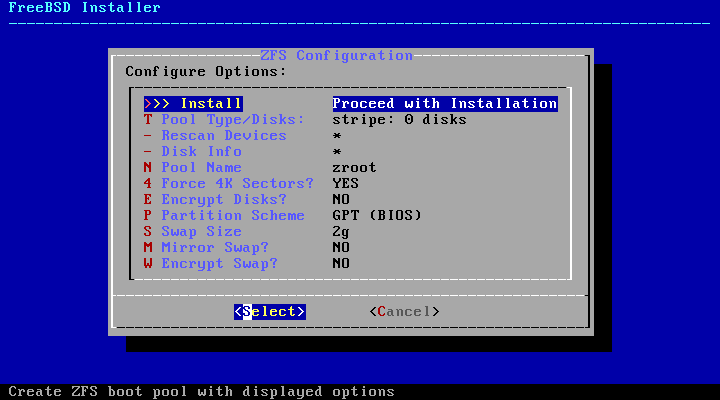

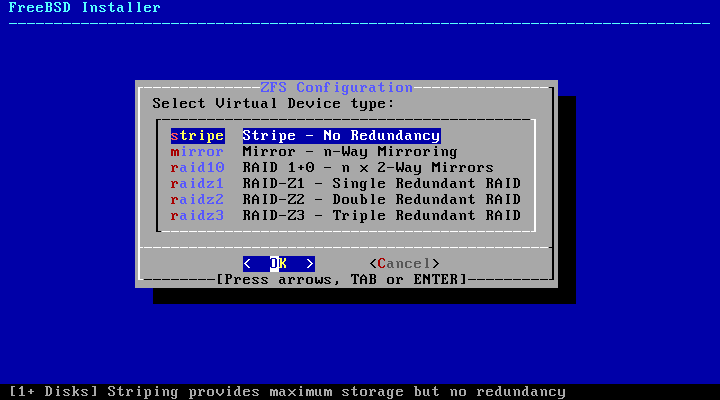

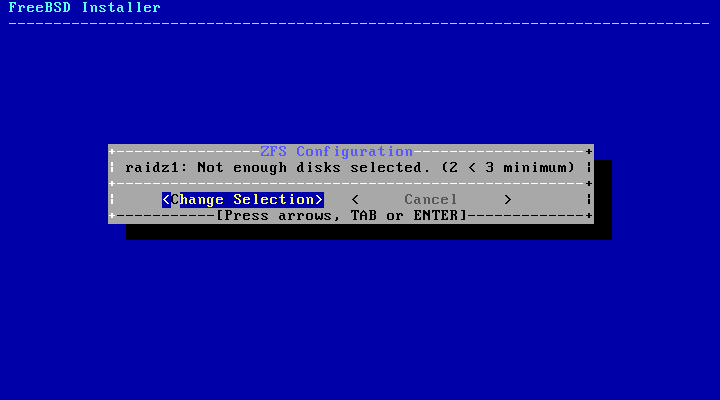

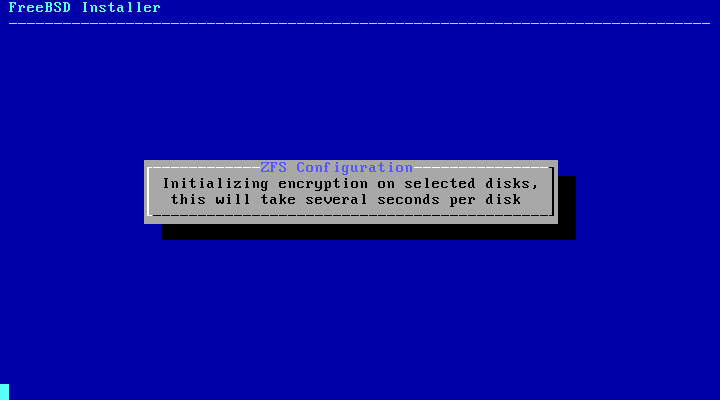

Auto (ZFS) partitioning creates a

root-on-ZFS system with optional GELI encryption support for

boot environments.

This section describes what to consider when laying out the

disk partitions. It then demonstrates how to use the different

partitioning methods.

2.6.1. Designing the Partition Layout

When laying out file systems, remember that hard drives

transfer data faster from the outer tracks to the inner.

Thus, smaller and heavier-accessed file systems should be

closer to the outside of the drive, while larger partitions

like /usr should be placed toward the

inner parts of the disk. It is a good idea to create

partitions in an order similar to: /,

swap, /var, and

/usr.

The size of the /var partition

reflects the intended machine's usage. This partition is

used to hold mailboxes, log files, and printer spools.

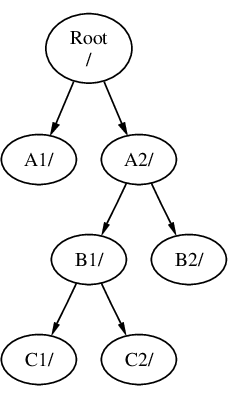

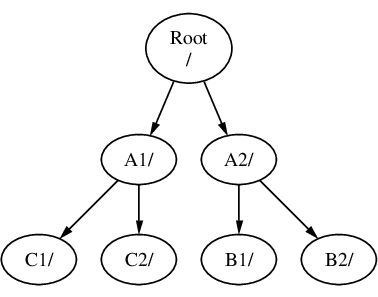

Mailboxes and log files can grow to unexpected sizes